Your Attitude May Not Get You Past 78.9

A couple of blogs ago, I mentioned that I started taking the advice of a large squadron of very successful writers, who have persuaded me that learning the craft of writing is “unglamorous blue-collar work” and that I should “just write.”

Duh!

So I’m holding fast to writing at least 500 words a day on something in my mental wheelhouse (positive aging, health and wellness, career/life management in the third age, etc.)

I’ve found the easiest way to hit that daily goal is to pick a question submitted on Quora.com which is, according to Wikipedia, “an American question-and-answer website where questions are asked, answered, and edited by Internet users, either factually or in the form of opinions.”

It’s been around since 2009 and has a user base of around 300 million active users.

I’ve been answering at least one question a day for a few months now and, quite shockingly, have had, as of this writing, over 885,000 views of my posts in Quora and achieved #1 Quora writer on the planet in one category (Longevity) and climbed into the top ten in two others (Health and Fitness).

It’ll be a tough position to hold but is a nice ego-stroke while it lasts.

////////////////

This Quora question hit my email this week:

“What should you do daily in order to live super healthy when you become 70?”

Smack into my wheelhouse!

I think my response is pretty good. Probably not good enough to go viral like one post did where I answered the question “What is the best anti-aging workout? It went viral with 445,000 Quora views.

I decided to let you determine if this latest one is good so I’m reposting it here for this week’s blog, with some modification and additions. You be the judge and let me know what you think.

P.S. If you’ve been tagging along with me on this 2 ½ year blogging journey, you’ve heard some of this before. But I believe “repetition is the mother of learning” still applies.

“What should you do daily in order to live super healthy when you become 70?”

The components of good health that will carry us into our 70s and beyond in good health are not complicated and we’ve known them for a long time. Sad to say, individually, we choose to be naive to them, find them too difficult and inconvenient and end up not doing them.

I suggest that the most important “daily” activity to insure being super healthy late into life is to remind ourselves each day that we have an inheritance of good health and an obligation to maintain it.

We aren’t inclined to put the components of good health – nutrition, exercise, social engagement, continuous learning, sense of purpose/service – in place without an attitude that honors this inheritance.

This point was driven home to me several years ago when I stumbled across the book “Dare to Be 100” written by Dr. Walter Bortz, a semi-retired Stanford University geriatric physician.

In this timeless book, he lays out a simple roadmap for good health using the acronym D-A-R-E:

- D=Diet

- A=Attitude

- R=Renewal/rejuvenation

- E=Exercise

The D, R, and E are biological compass points for living to 100 (which, BTW, we all should be able to do). But attitude is the most important and the most difficult because, as Dr. Bortz says, “it’s in attitude that we find all the planning and decision-making that facilitate the biological steps. It is possible to live to 100 by chance, but not likely.”

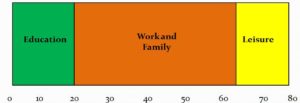

So living healthily into our 70s and beyond isn’t going to happen by chance either and will only happen with a commitment to a discipline that builds the simple components of diet, exercise, social engagement, having a cause bigger than yourself, and continuous learning into a lifestyle.

It’s important to remember that there is no biological reason for any of us not to live to 100 or beyond.

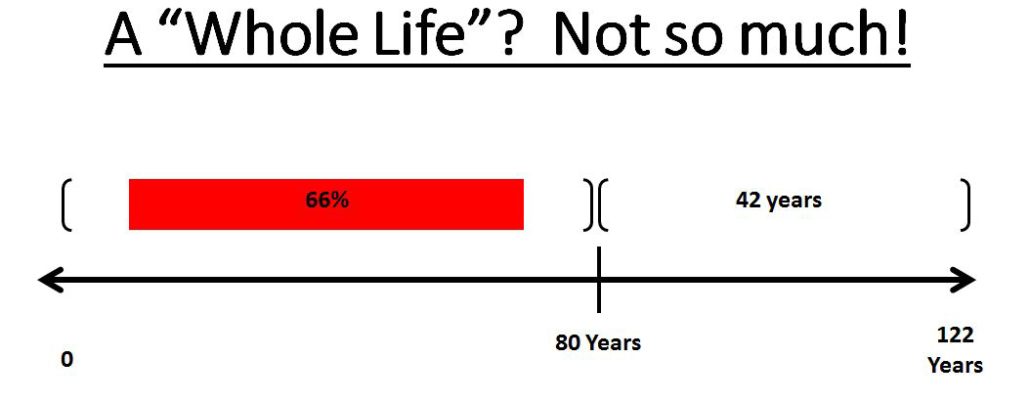

The body has demonstrated that it can last 122 years and 164 days which is the benchmark for longevity set by a Parisian woman named Jeanne Calment. (Yeah, I know – you may have heard that this has been debunked. Look again – the debunking has been debunked.)

The right attitude acknowledges this as our whole-life potential and the inheritance that we should honor.

Will we get to 122 1/2? Not likely. But with an attitude that acknowledges that the body is designed for a longer life than we experience on average, we enhance our chances of getting closer to it than if we accept that average life span as our destiny.

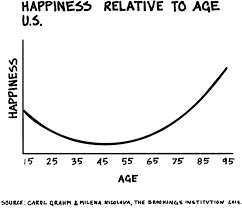

On average, at an overall average lifespan in the U.S. of around 80 (78.9 for men, 81.1 for women), we achieve only about 66% of that “whole life potential.”

With the exception of the consequences of the infrequent “blueprint error/genetic defect”, we die early in our culture simply because of our lifestyles. Our declines as we move into our 60s and 70s are thirty-year problems of lifestyle, not disease. We are more victims of our own healthcare illiteracy and lack of discipline than anything else.

Let me quote Dr. Henry Lodge, co-author of the best-selling and life-changing book “Younger Next Year: Live Strong, Fit and Sexy – Until You’re 80 and Beyond”.

“The simple fact is that we know perfectly well what to do. Some 70 percent of premature death and aging are lifestyle-related. Heart attacks, strokes, the common cancers, diabetes, most falls, fractures, and serious injuries, and many more illnesses are primarily caused by the way we live. If we had the will to do it, we could eliminate more than half of all disease in men and women over fifty. Not delay it, eliminate it.”

I believe that statement has attitude written all over it, as well as a call to learn about our biological inheritance, how it works and how to treat it.

I’m two months short of 78 and approach each day with an acquired understanding of how my body and mind work at the cellular level (thanks to Dr. Lodge). I set a preposterous age goal of 112 ½ at age 75 because I wanted a third of my life left to get things done that didn’t happen in the first two-thirds.

I have no illusions about getting there. I was guilty of some marginal health habits in my first fifty years and before I acquired this self-care awareness. But I know my attitude will get me a lot closer – and healthier along the way – than if I accepted only living to the average lifespan of 78.9 for men in the U.S.

If that were my attitude, I should be getting my affairs in order – which I’m not. I don’t need that drag on my attitude.

Average isn’t healthy

I started re-reading “Younger Next Year” again this week for the fifth time. It was good to be reminded of Dr. Lodge’s description of how he watched so many of his patients of 20-30 years simply start a gradual decline and accept an average lifespan as destiny.

He realized that he, along with our medical establishment, had failed them by providing them with good medical care but not great health care. He admitted that he “like most doctors in America, had been doing the wrong job well. Modern medicine does not concern itself with lifestyle problems. Doctors don’t treat them, medical schools don’t teach them and insurers don’t pay to solve them.”

We forget – or didn’t learn along the way – that what we’ve come to accept as normal ailments and deterioration are not a normal part of growing old. In Dr. Lodge’s words “they are an outrage. An outrage that we have simply gotten used to because we set the bar so shamefully low.” (See “Whole-life chart above!)

I’m going to ignore 78.9 as it flies by, which it will as each day does now. It’s just an attitude, accepting of an eventual demise but not one conceding to a “bar set so shamefully low.”

How’s your attitude about your long-term health?

- Is it infected with illiteracy about how your biology works? (Remedy: Chapters 3 & 4 of Younger Next Year)

- Is it infected with a belief that your “DNA is your destiny” or that your genetics determines your lifespan (which, BTW, it does not.)

- Is it infected with lifestyle habits spawned by comfort, convenience, conformity, and cultural expectations?

- Is it infected with a longevity goal “set so shamefully low?”

Can I suggest that 78.9 should be just a signpost reminding you that you are well beyond average and that it is merely a mid-point in your healthy third-age journey to 100 or beyond?

As I immersed myself this morning in the challenging chapter 3 of “Younger Next Year”, Dr. Lodge rocked my world for the fifth time with the reminder that we have “- stepped outside of the crucible of our biological evolution” and with a “- remarkable triumph of ego over intellect, we simply assume that we were ‘made’ for this life: that we were purpose-built for life in the twenty-first century. That is a deeply mistaken view, and one we must get over.”

He reminds us that the great problem of our times is “surfeit (excess abundance) and idleness” with bodies and minds that still instinctively respond to the abundance as preparation for famine as we did 300 millennia ago when we barely survived winters and hid from saber-tooths. Now, no famine is coming but our biology hasn’t caught up with change.

He reminds us that the great problem of our times is “surfeit (excess abundance) and idleness” with bodies and minds that still instinctively respond to the abundance as preparation for famine as we did 300 millennia ago when we barely survived winters and hid from saber-tooths. Now, no famine is coming but our biology hasn’t caught up with change.

We have lots to eat with nothing that can eat us.

He concludes:

“Our lifestyle – especially in retirement, especially in this wonderful country – is a disease more deadly than cancer, war or plague. We live longer because of modern medicine, but many of us live wretchedly and many of us die much younger than we should. The point is that we have to learn to cure ourselves, or, in the midst of all that plenty, we will live and prematurely die in unnecessary pain – in bodies that believe they are in the grip of famine.”

If you’ve read the book (please don’t tell me you haven’t!), you know that Dr. Lodge’s main solution is exercise and that he does a marvelous job of convincing readers of the validity of that recommendation by explaining its impact at the cellular level.

From it, we have “Harry’s Rules” which I leave as the call to action with this article (along with reading the book), to help us all get well past 78.9 and 81.1. Without an attitude committing to something like this, that is likely to be our fate.

Harry’s Rules

- Exercise six days a week for the rest of your life.

- Do serious aerobic exercise four days a week for the rest of your life.

- Do serious strength training, with weights, two days a week for the rest of your life.

- Spend less than you make.

- Quit eating crap!

- Care.

- Connect and commit.

Let me know your thoughts – scroll down and leave a comment.

Our tribe is growing rapidly, thanks to your consistent support and spreading the word along with folks catching my diatribes on Quora. If you haven’t joined, trip on over to www.makeagingwork.com, join the list and receive a copy of my free ebook “Achieving Your Full-life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

OK, I’m sure you did the math: 9 years minus 5 ½ years = 3 ½ years. Yep – a full third of a decade between college stints spent in aimless wandering and squandering while I confirmed that the male brain doesn’t reach maturity until around age 24 which was when I returned to campus for the final run.

OK, I’m sure you did the math: 9 years minus 5 ½ years = 3 ½ years. Yep – a full third of a decade between college stints spent in aimless wandering and squandering while I confirmed that the male brain doesn’t reach maturity until around age 24 which was when I returned to campus for the final run.

Thinking about your thinking

Thinking about your thinking

Take the big words, all the research, the eloquent language, the checklists and it all returns back to one thing which Hagerty uses as the chapter title – “It’s The Thought That Counts.”

Take the big words, all the research, the eloquent language, the checklists and it all returns back to one thing which Hagerty uses as the chapter title – “It’s The Thought That Counts.”

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.