WARNING! Retirement May Mess With Your Oligodencrocytes!

Oligo what?

Hey, I didn’t know we had them, did you? Yet another something in the “cytes” category roaming around our bodies.

I found out I had oligodencrocytes as I was slogging through my second reading of a challenging book entitled “Deep Work; Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World” by Georgetown University computer science professor, Cal Newport.

I bought the book in hopes of finding an inexpensive antidote to my ADD and “shiny object syndrome.”

I’m thinking 3-4 times through this book will have saved me the stigma and expense of the therapy I really need.

So it was that on page 36 of “Deep Work”, I found out that I have oligodencrocytes. We all do.

Why should we care?

Well, we don’t have to – and most people don’t. Can we survive without them? Probably not. I’m no expert, but I believe that if you don’t have them at some level, you are dead.

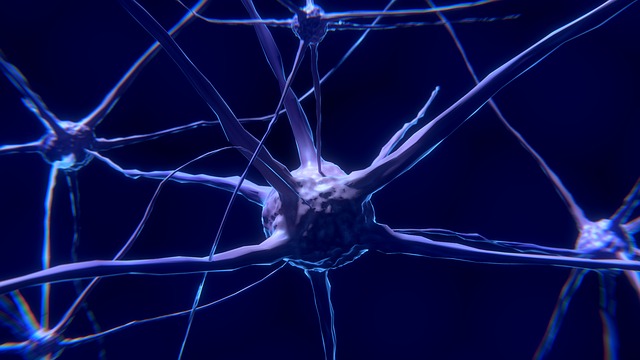

To understand oligodencrocytes, what they do and why they are important, we have to climb a notch higher in basic neurology and understand that we have a process going on in our brain called myelination.

It turns out our brain produces a fatty tissue called myelin that wraps around neurons as we use them, acting like an insulator that allows that neuron’s cells to fire cleaner and faster. Oligodencrocytes are cells that trigger that myelin. The more you use a neural circuit, the more “olis” you have that are producing more myelin to wrap and thicken that circuit.

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.

I’m likely butchering the neurological description, but I think it’s safe to say that each of us has, between our temples, a labyrinth of skinny, semi-thick and (maybe) thick neuronal circuits. All determined by WHAT we think about and HOW MUCH we think about that WHAT.

The more we use a neural circuit to focus on one particular idea or activity, the more “olis” we ignite to help wrap another layer of myelin around that circuit.

Thick or thin?

Most of us are walking around with a mess of thin and semi-thick neuronal circuits. Few of us have really thick circuits. And then we marvel at – or maybe even resent – the prolific perfection of Tiger Woods, Daniel Day-Lewis, YoYo Ma, Stephen King, Jerry Rice, etc., not understanding that they simply have myelinated themselves to a very small number of very thick neuronal circuits – by what they think about and do every day, in-depth, deliberately.

I first became aware of the significance of myelination having read about it ten years ago in an excerpt from the 2008 book by Fortune editor Geoff Colvin entitled “Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else”. With my curiosity peaked by the boldness of the title, I subsequently read Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers: The Story of Success” and Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown”.

All three books talk about the significant role of myelination in achieving success and mastery. The message from the books – and subsequently confirmed by tons of data and research – is that there are no prodigies, only “deep work” and “deliberate practice” behind the outliers on the performance and success scales.

In other words, high achievers are prolific “oli” and myelin generators. By choice and design, not by chance.

When I first read about this years ago, I remember I had just decided that I was going to learn to play fingerstyle acoustic guitar after avoiding it for 40+ years of playing only plectrum-style jazz guitar. I had dabbled a bit with it but found it took too much effort and was a distraction from my love for learning and playing jazz ballads.

But then I discovered an Australian guitarist by the name of Tommy Emmanuel when someone sent me a link to a YouTube recording of him playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.

I was immediately mentally transformed. I could no longer reject the challenge of learning fingerstyle having witnessed it performed by a master. I decided to become a student of Tommy Emmanuel, which included not just learning technique from his CD, DVD, and online tutorials but also understanding him as a person (I’ve met him twice), what drives him and what it took for him to become what most consider to be the best acoustic guitar player on the planet.

As I struggled to make both hands do what felt very unnatural and uncomfortable while asking my brain to sync them up, I began to appreciate that this wasn’t going to happen without some serious myelination which, in turn, wasn’t going to happen without serious “deep work” and “deliberate practice”.

As I immersed myself in Tommy’s world, I set a goal of learning 10% of what he has forgotten, knowing that if I did just that, I would have put myself at a level achieved by few guitar players.

Tommy Emmanuel is highly myelinated. As I write, he is 64. He started playing guitar at age 4 and hasn’t looked back; he taught himself from Chet Atkins records and subsequently become one of four guitarists in the world to be designated “Certified Guitar Player” by Chet; he performs 300 days a year globally, practices every day and vows “to be better tomorrow than I am today.”

I can just imagine the thickness of that neural circuit and the number of “olis” he’s burned through to have his brain and hands do the seemingly impossible.

Myelin isn’t permanent.

I’ve learned another thing about myelin along the way. It isn’t permanent. After several years of pretty disciplined deep and deliberate practice on the acoustic guitar, I’ve had to set it aside for the last several months due to a painful arthritic condition in my left thumb, a vital digit for trying to mimic Tommy Emmanuel.

Any attempt to resurrect a favorite Tommy song on my 1966 Gibson Hummingbird only generates frustration on top of the pain since it’s too painful to complete any of the songs I worked so hard to learn. It will require a joint replacement. a restart, and another commitment to deep work and deliberate practice to get back.

That once relatively thick neuronal circuit has gone skinny.

I’ll get it back. In the meantime, I’m stimulating my “olis” and myelinating another circuit – my writing circuit.

I’ll get it back. In the meantime, I’m stimulating my “olis” and myelinating another circuit – my writing circuit.

I haven’t done serious research on “olis” but I’m pretty confident that they will stay with me as long as I want to put them to work. I know that I can build new neurons as long as I live if I work at it. I believe scientists called it “neurogenesis”. I take that to mean I’ve got “olis” ready to do their thing if I’ll activate them.

Dr. Roger Landry, preventive medicine physician, former Air Force flight surgeon and author of “Live Long, Die Short: A Guide to Authentic Health and Successful Aging” points out that:

” Atrophy of the brain used to be viewed as a side effect of aging. Now, we know this may simply be a lack of use. When we use the skills and knowledge we have, the many connections in the brain remain in the best shape they can be. Don’t use them, and they become more difficult to use through a process known as synaptic pruning, in which the brain atrophies in areas where these functions are rarely used. Neuroplasticity and effective neurogenesis can only occur when the brain is stimulated by environment or behavior.”

There you have it – my Tommy Emmanual channel is being”synaptically pruned”.

Is retirement good for your oligodencrocytes?

The last sentence in Dr. Landry’s quote took me back to a number of retirement conversations I’ve had over the last year with recently retired or soon-to-be-retired C-level healthcare executives. Boredom is one of the most common concerns expressed by these high-functioning leaders as they enter this phase of life.

I think I’m within reasonable neurological boundaries to say that boredom is a lack of neurogenesis because retirement, for most, is a transition from an environment where the “brain is stimulated by environment and behavior” along with active oligodencrocyte/myelin production to one that starts skinnying up some pretty valuable neuronal circuits.

A multi-decade investment of “olis” and myelin is allowed to waste away. A new imbalance of leisure versus learning kicks in that isn’t conducive to maintaining or cranking that biological partnership back up to form newer thick circuits.

In other words, retirement may mess with your oligodencrocytes – and, in turn, with your myelination and enable “synaptic pruning” to take thick back to thin.

I wouldn’t want to infer that retirement may end up wasting a lot of talent, wisdom, and experience, but – – – well, OK, that’s exactly what I’m saying!

Hey, I get it if you have zero interest in re-myelinating some of the circuits that you myelinated for decades in your job, more out of necessity than desire. Like herding the cats that were your staff. Or pushing through unrealistic budget creation. Or jousting with board members. Or writing grant proposals. Or – – – – – –

– – -you know what you were good at then that you don’t want to do more of.

But embedded in all that accumulated experience and talent deployment, I’ll just bet there are some residual semi-thick circuits that still fire your jets, screaming for a dose of “olis”, ready to myelinate.

Drifting into retirement without a non-financial plan – which 2 of 3 new retirees do – sets the stage for dormant “olis” and de-myelination at a time when the combination of wisdom, experience, and talent are at optimum levels.

I think we can agree that life is essentially just a series of choices. The cultural influences affecting the retirement or third age phase of life often lead us to choices counter to our biology and neurology.

Brain atrophy (READ: de-myelination) is one of those choices.

It’s a time for a new take-off, not a landing. And your “olis” and myelin stand ready to help the re-launch.

I would love your comments. Scroll down and let me know what you think. If you haven’t signed up for my weekly articles like this one, you can do so at www.makeagingwork.com. When you join our rapidly growing “tribe”, I’ll send you a free e-book entitled “Achieve Your Full-life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Have an outrageous 2020!!