Oligo what?

Hey, I didn’t know we had them, did you? Yet another something in the “cytes” category roaming around our bodies.

I found out I had oligodencrocytes as I was slogging through my second reading of a challenging book entitled “Deep Work; Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World” by Georgetown University computer science professor, Cal Newport.

I bought the book in hopes of finding an inexpensive antidote to my ADD and “shiny object syndrome.”

I’m thinking 3-4 times through this book will have saved me the stigma and expense of the therapy I really need.

So it was that on page 36 of “Deep Work”, I found out that I have oligodencrocytes. We all do.

Why should we care?

Well, we don’t have to – and most people don’t. Can we survive without them? Probably not. I’m no expert, but I believe that if you don’t have them at some level, you are dead.

To understand oligodencrocytes, what they do and why they are important, we have to climb a notch higher in basic neurology and understand that we have a process going on in our brain called myelination.

It turns out our brain produces a fatty tissue called myelin that wraps around neurons as we use them, acting like an insulator that allows that neuron’s cells to fire cleaner and faster. Oligodencrocytes are cells that trigger that myelin. The more you use a neural circuit, the more “olis” you have that are producing more myelin to wrap and thicken that circuit.

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.

I’m now thinking these little “oli” rascals are pretty darn important in where we end up in life. And all this time I didn’t know they were there standing ready to help dismantle my self-inflicted ADD.

I’m likely butchering the neurological description, but I think it’s safe to say that each of us has, between our temples, a labyrinth of skinny, semi-thick and (maybe) thick neuronal circuits. All determined by WHAT we think about and HOW MUCH we think about that WHAT.

The more we use a neural circuit to focus on one particular idea or activity, the more “olis” we ignite to help wrap another layer of myelin around that circuit.

Thick or thin?

Most of us are walking around with a mess of thin and semi-thick neuronal circuits. Few of us have really thick circuits. And then we marvel at – or maybe even resent – the prolific perfection of Tiger Woods, Daniel Day-Lewis, YoYo Ma, Stephen King, Jerry Rice, etc., not understanding that they simply have myelinated themselves to a very small number of very thick neuronal circuits – by what they think about and do every day, in-depth, deliberately.

I first became aware of the significance of myelination having read about it ten years ago in an excerpt from the 2008 book by Fortune editor Geoff Colvin entitled “Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else”. With my curiosity peaked by the boldness of the title, I subsequently read Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers: The Story of Success” and Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown”.

All three books talk about the significant role of myelination in achieving success and mastery. The message from the books – and subsequently confirmed by tons of data and research – is that there are no prodigies, only “deep work” and “deliberate practice” behind the outliers on the performance and success scales.

In other words, high achievers are prolific “oli” and myelin generators. By choice and design, not by chance.

When I first read about this years ago, I remember I had just decided that I was going to learn to play fingerstyle acoustic guitar after avoiding it for 40+ years of playing only plectrum-style jazz guitar. I had dabbled a bit with it but found it took too much effort and was a distraction from my love for learning and playing jazz ballads.

But then I discovered an Australian guitarist by the name of Tommy Emmanuel when someone sent me a link to a YouTube recording of him playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.

I was immediately mentally transformed. I could no longer reject the challenge of learning fingerstyle having witnessed it performed by a master. I decided to become a student of Tommy Emmanuel, which included not just learning technique from his CD, DVD, and online tutorials but also understanding him as a person (I’ve met him twice), what drives him and what it took for him to become what most consider to be the best acoustic guitar player on the planet.

As I struggled to make both hands do what felt very unnatural and uncomfortable while asking my brain to sync them up, I began to appreciate that this wasn’t going to happen without some serious myelination which, in turn, wasn’t going to happen without serious “deep work” and “deliberate practice”.

As I immersed myself in Tommy’s world, I set a goal of learning 10% of what he has forgotten, knowing that if I did just that, I would have put myself at a level achieved by few guitar players.

Tommy Emmanuel is highly myelinated. As I write, he is 64. He started playing guitar at age 4 and hasn’t looked back; he taught himself from Chet Atkins records and subsequently become one of four guitarists in the world to be designated “Certified Guitar Player” by Chet; he performs 300 days a year globally, practices every day and vows “to be better tomorrow than I am today.”

I can just imagine the thickness of that neural circuit and the number of “olis” he’s burned through to have his brain and hands do the seemingly impossible.

Myelin isn’t permanent.

I’ve learned another thing about myelin along the way. It isn’t permanent. After several years of pretty disciplined deep and deliberate practice on the acoustic guitar, I’ve had to set it aside for the last several months due to a painful arthritic condition in my left thumb, a vital digit for trying to mimic Tommy Emmanuel.

Any attempt to resurrect a favorite Tommy song on my 1966 Gibson Hummingbird only generates frustration on top of the pain since it’s too painful to complete any of the songs I worked so hard to learn. It will require a joint replacement. a restart, and another commitment to deep work and deliberate practice to get back.

That once relatively thick neuronal circuit has gone skinny.

I’ll get it back. In the meantime, I’m stimulating my “olis” and myelinating another circuit – my writing circuit.

I’ll get it back. In the meantime, I’m stimulating my “olis” and myelinating another circuit – my writing circuit.

I haven’t done serious research on “olis” but I’m pretty confident that they will stay with me as long as I want to put them to work. I know that I can build new neurons as long as I live if I work at it. I believe scientists called it “neurogenesis”. I take that to mean I’ve got “olis” ready to do their thing if I’ll activate them.

Dr. Roger Landry, preventive medicine physician, former Air Force flight surgeon and author of “Live Long, Die Short: A Guide to Authentic Health and Successful Aging” points out that:

” Atrophy of the brain used to be viewed as a side effect of aging. Now, we know this may simply be a lack of use. When we use the skills and knowledge we have, the many connections in the brain remain in the best shape they can be. Don’t use them, and they become more difficult to use through a process known as synaptic pruning, in which the brain atrophies in areas where these functions are rarely used. Neuroplasticity and effective neurogenesis can only occur when the brain is stimulated by environment or behavior.”

There you have it – my Tommy Emmanual channel is being”synaptically pruned”.

Is retirement good for your oligodencrocytes?

The last sentence in Dr. Landry’s quote took me back to a number of retirement conversations I’ve had over the last year with recently retired or soon-to-be-retired C-level healthcare executives. Boredom is one of the most common concerns expressed by these high-functioning leaders as they enter this phase of life.

I think I’m within reasonable neurological boundaries to say that boredom is a lack of neurogenesis because retirement, for most, is a transition from an environment where the “brain is stimulated by environment and behavior” along with active oligodencrocyte/myelin production to one that starts skinnying up some pretty valuable neuronal circuits.

A multi-decade investment of “olis” and myelin is allowed to waste away. A new imbalance of leisure versus learning kicks in that isn’t conducive to maintaining or cranking that biological partnership back up to form newer thick circuits.

In other words, retirement may mess with your oligodencrocytes – and, in turn, with your myelination and enable “synaptic pruning” to take thick back to thin.

I wouldn’t want to infer that retirement may end up wasting a lot of talent, wisdom, and experience, but – – – well, OK, that’s exactly what I’m saying!

Hey, I get it if you have zero interest in re-myelinating some of the circuits that you myelinated for decades in your job, more out of necessity than desire. Like herding the cats that were your staff. Or pushing through unrealistic budget creation. Or jousting with board members. Or writing grant proposals. Or – – – – – –

– – -you know what you were good at then that you don’t want to do more of.

But embedded in all that accumulated experience and talent deployment, I’ll just bet there are some residual semi-thick circuits that still fire your jets, screaming for a dose of “olis”, ready to myelinate.

Drifting into retirement without a non-financial plan – which 2 of 3 new retirees do – sets the stage for dormant “olis” and de-myelination at a time when the combination of wisdom, experience, and talent are at optimum levels.

I think we can agree that life is essentially just a series of choices. The cultural influences affecting the retirement or third age phase of life often lead us to choices counter to our biology and neurology.

Brain atrophy (READ: de-myelination) is one of those choices.

It’s a time for a new take-off, not a landing. And your “olis” and myelin stand ready to help the re-launch.

I would love your comments. Scroll down and let me know what you think. If you haven’t signed up for my weekly articles like this one, you can do so at www.makeagingwork.com. When you join our rapidly growing “tribe”, I’ll send you a free e-book entitled “Achieve Your Full-life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Have an outrageous 2020!!

WARNING! Retirement May Mess With Your Oligodencrocytes!

Oligo what?

Hey, I didn’t know we had them, did you? Yet another something in the “cytes” category roaming around our bodies.

I found out I had oligodencrocytes as I was slogging through my second reading of a challenging book entitled “Deep Work; Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World” by Georgetown University computer science professor, Cal Newport.

I bought the book in hopes of finding an inexpensive antidote to my ADD and “shiny object syndrome.”

I’m thinking 3-4 times through this book will have saved me the stigma and expense of the therapy I really need.

So it was that on page 36 of “Deep Work”, I found out that I have oligodencrocytes. We all do.

Why should we care?

Well, we don’t have to – and most people don’t. Can we survive without them? Probably not. I’m no expert, but I believe that if you don’t have them at some level, you are dead.

To understand oligodencrocytes, what they do and why they are important, we have to climb a notch higher in basic neurology and understand that we have a process going on in our brain called myelination.

It turns out our brain produces a fatty tissue called myelin that wraps around neurons as we use them, acting like an insulator that allows that neuron’s cells to fire cleaner and faster. Oligodencrocytes are cells that trigger that myelin. The more you use a neural circuit, the more “olis” you have that are producing more myelin to wrap and thicken that circuit.

I’m likely butchering the neurological description, but I think it’s safe to say that each of us has, between our temples, a labyrinth of skinny, semi-thick and (maybe) thick neuronal circuits. All determined by WHAT we think about and HOW MUCH we think about that WHAT.

The more we use a neural circuit to focus on one particular idea or activity, the more “olis” we ignite to help wrap another layer of myelin around that circuit.

Thick or thin?

Most of us are walking around with a mess of thin and semi-thick neuronal circuits. Few of us have really thick circuits. And then we marvel at – or maybe even resent – the prolific perfection of Tiger Woods, Daniel Day-Lewis, YoYo Ma, Stephen King, Jerry Rice, etc., not understanding that they simply have myelinated themselves to a very small number of very thick neuronal circuits – by what they think about and do every day, in-depth, deliberately.

I first became aware of the significance of myelination having read about it ten years ago in an excerpt from the 2008 book by Fortune editor Geoff Colvin entitled “Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else”. With my curiosity peaked by the boldness of the title, I subsequently read Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers: The Story of Success” and Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown”.

All three books talk about the significant role of myelination in achieving success and mastery. The message from the books – and subsequently confirmed by tons of data and research – is that there are no prodigies, only “deep work” and “deliberate practice” behind the outliers on the performance and success scales.

In other words, high achievers are prolific “oli” and myelin generators. By choice and design, not by chance.

When I first read about this years ago, I remember I had just decided that I was going to learn to play fingerstyle acoustic guitar after avoiding it for 40+ years of playing only plectrum-style jazz guitar. I had dabbled a bit with it but found it took too much effort and was a distraction from my love for learning and playing jazz ballads.

But then I discovered an Australian guitarist by the name of Tommy Emmanuel when someone sent me a link to a YouTube recording of him playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.

I was immediately mentally transformed. I could no longer reject the challenge of learning fingerstyle having witnessed it performed by a master. I decided to become a student of Tommy Emmanuel, which included not just learning technique from his CD, DVD, and online tutorials but also understanding him as a person (I’ve met him twice), what drives him and what it took for him to become what most consider to be the best acoustic guitar player on the planet.

As I struggled to make both hands do what felt very unnatural and uncomfortable while asking my brain to sync them up, I began to appreciate that this wasn’t going to happen without some serious myelination which, in turn, wasn’t going to happen without serious “deep work” and “deliberate practice”.

As I immersed myself in Tommy’s world, I set a goal of learning 10% of what he has forgotten, knowing that if I did just that, I would have put myself at a level achieved by few guitar players.

Tommy Emmanuel is highly myelinated. As I write, he is 64. He started playing guitar at age 4 and hasn’t looked back; he taught himself from Chet Atkins records and subsequently become one of four guitarists in the world to be designated “Certified Guitar Player” by Chet; he performs 300 days a year globally, practices every day and vows “to be better tomorrow than I am today.”

I can just imagine the thickness of that neural circuit and the number of “olis” he’s burned through to have his brain and hands do the seemingly impossible.

Myelin isn’t permanent.

I’ve learned another thing about myelin along the way. It isn’t permanent. After several years of pretty disciplined deep and deliberate practice on the acoustic guitar, I’ve had to set it aside for the last several months due to a painful arthritic condition in my left thumb, a vital digit for trying to mimic Tommy Emmanuel.

Any attempt to resurrect a favorite Tommy song on my 1966 Gibson Hummingbird only generates frustration on top of the pain since it’s too painful to complete any of the songs I worked so hard to learn. It will require a joint replacement. a restart, and another commitment to deep work and deliberate practice to get back.

That once relatively thick neuronal circuit has gone skinny.

I haven’t done serious research on “olis” but I’m pretty confident that they will stay with me as long as I want to put them to work. I know that I can build new neurons as long as I live if I work at it. I believe scientists called it “neurogenesis”. I take that to mean I’ve got “olis” ready to do their thing if I’ll activate them.

Dr. Roger Landry, preventive medicine physician, former Air Force flight surgeon and author of “Live Long, Die Short: A Guide to Authentic Health and Successful Aging” points out that:

” Atrophy of the brain used to be viewed as a side effect of aging. Now, we know this may simply be a lack of use. When we use the skills and knowledge we have, the many connections in the brain remain in the best shape they can be. Don’t use them, and they become more difficult to use through a process known as synaptic pruning, in which the brain atrophies in areas where these functions are rarely used. Neuroplasticity and effective neurogenesis can only occur when the brain is stimulated by environment or behavior.”

There you have it – my Tommy Emmanual channel is being”synaptically pruned”.

Is retirement good for your oligodencrocytes?

The last sentence in Dr. Landry’s quote took me back to a number of retirement conversations I’ve had over the last year with recently retired or soon-to-be-retired C-level healthcare executives. Boredom is one of the most common concerns expressed by these high-functioning leaders as they enter this phase of life.

I think I’m within reasonable neurological boundaries to say that boredom is a lack of neurogenesis because retirement, for most, is a transition from an environment where the “brain is stimulated by environment and behavior” along with active oligodencrocyte/myelin production to one that starts skinnying up some pretty valuable neuronal circuits.

A multi-decade investment of “olis” and myelin is allowed to waste away. A new imbalance of leisure versus learning kicks in that isn’t conducive to maintaining or cranking that biological partnership back up to form newer thick circuits.

In other words, retirement may mess with your oligodencrocytes – and, in turn, with your myelination and enable “synaptic pruning” to take thick back to thin.

I wouldn’t want to infer that retirement may end up wasting a lot of talent, wisdom, and experience, but – – – well, OK, that’s exactly what I’m saying!

Hey, I get it if you have zero interest in re-myelinating some of the circuits that you myelinated for decades in your job, more out of necessity than desire. Like herding the cats that were your staff. Or pushing through unrealistic budget creation. Or jousting with board members. Or writing grant proposals. Or – – – – – –

– – -you know what you were good at then that you don’t want to do more of.

But embedded in all that accumulated experience and talent deployment, I’ll just bet there are some residual semi-thick circuits that still fire your jets, screaming for a dose of “olis”, ready to myelinate.

Drifting into retirement without a non-financial plan – which 2 of 3 new retirees do – sets the stage for dormant “olis” and de-myelination at a time when the combination of wisdom, experience, and talent are at optimum levels.

I think we can agree that life is essentially just a series of choices. The cultural influences affecting the retirement or third age phase of life often lead us to choices counter to our biology and neurology.

Brain atrophy (READ: de-myelination) is one of those choices.

It’s a time for a new take-off, not a landing. And your “olis” and myelin stand ready to help the re-launch.

I would love your comments. Scroll down and let me know what you think. If you haven’t signed up for my weekly articles like this one, you can do so at www.makeagingwork.com. When you join our rapidly growing “tribe”, I’ll send you a free e-book entitled “Achieve Your Full-life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Have an outrageous 2020!!

A Life Lesson Learned from a Thomasville Chair

2019 contained a lost summer for my wife and me. We decided to move from home-ownership to the rental world temporarily, in defiance of all conventional advice regarding balance sheet/net worth/equity/tax benefits, yada, yada, yada.

For a couple of months, we battled the remorse of leaving a large comfortable home on the 10th fairway of a semi-private golf course with this as a “backyard”:

But we faced an expensive upgrade or go. We decided to go – let the next owners endure the inconvenience and expense.

We’ve both been surprised at how quickly we got over the remorse as we’ve finally settled into a very comfortable home 2/3 the size of the one we left.

June through August was lost to making the move, a lot of which we did on our own in the midst of one of the hottest Colorado summers on record. (Note to self: don’t EVER try that again!).

We anxiously waited for offers to come in on the house as we began the move, risking having to pay rent plus mortgage for an extended period.

We were lucky – the overlap was minimal.

We came close to catching the peak of a hot real estate market that we sensed was running its course, missing the absolute peak by about six weeks. So we did OK in maximizing our “equity capture.”

A moving experience

You’ve heard or read the stories of what it’s like to downsize, purge, declutter, etc. We are not, and never have been extravagant or major accumulators. But 49 years of marriage and family-living creates a mind-warping collection of “stuff”.

Un-stuffing is tough – and not a lot of fun.

NEWSFLASH: Nobody wants or needs your “stuff”.

Our purge was spread over 45 days of innumerable trips to Goodwill, ARC, Salvation Army along with numerous large curbside collections of “un-donatables”. Somehow we made what remained all fit into this smaller home.

It’s still way too much stuff. It’s hard to imagine another 1/3 to 1/2 downsize for our next – and likely last – move.

Did we learn anything?

This morning, in my cramped office, I found myself reflecting back on the experience and wondering: “Was there a life lesson in this drawn-out event?”

Don’t ask me to explain it, but my thoughts went to a Thomasville chair – a white-on-white, $1,200 (Y2K dollars), 4’x6’ chair-ottoman combination (the picture at the top is the real thing) that sat in our master bedroom for 19 years.

We estimate it experienced either one of our behinds less than 20 times in those 19 years! Seriously.

How hard was it to let go of emotionally? Near zero!

Was it hard to get rid of physically? Yep. No Craig’s List responses. Upscale consignment store laughed us out the front door: “Uh, 4’x6’, white-on-white? What century are you from?”

Oh, and you may already know that ARC, Salvation Army, Goodwill, et.al aren’t keen on taking furniture. We got creative at finding alternate access and dumping some lesser stuff at night.

We considered putting the chair curbside with a $50 sign on it, thus ensuring it would be stolen in the night, but our egos and a sliver of respect for our neighbors killed that idea.

So, in her perennially persistent manner, my wife found a “lesser” consignment store who agree to take it.

It went on the consignment floor for $199 with a written contract that stipulated a declining price each month along with a usurious percentage of the proceeds and the agreement that if not sold within three months, it would be given away or otherwise disposed of.

Well, surprise, surprise – it sold! On the day it hit the final reduced price on the floor – from which our proceeds were zero!

Scammed. Hoodwinked. Gullible. Hijacked. These are just a few of the words that came to me when we received the notice.

But then I rethought those retorts. What made me think I needed a $1,200 name brand chair that got sat in maybe once every six months for 19 years anyway?

You’ve come a long way – maybe!

As I looked around our current digs with its reduced footprint but still way too much “stuff”, my thoughts drifted to my maternal grandparent’s 1200 sq.ft. concrete house that they built by hand when they homesteaded in southeastern Wyoming 110 years ago (the real house pictured below).

They lived in a dugout for a year while they built the house. During much of that building year, they carried water by hand from a neighbor’s well a half-mile away as they dug their own well.

They occupied that house until they died.

They delivered four children there (one lost to scarlet fever as a teenager) and scratched out a bare subsistence on 160-acres of hardscrabble land granted them by the government to attract them to come further west from Nebraska.

I spent lots of time in that house growing up although our family lived in town ten miles away. I remember grandma pumping water by hand in her modest kitchen and cooking and baking on a coal-fired cast iron stove. Gramps was dawn to dusk, 7x, keeping animals alive and tools working and taking from the animals what they innocently relinquished.

The house was heated, quite poorly, by burning coal in a pot-belly stove in a small living room. Winters were an adventure.

Entertainment was a radio. Social life was all about church in a nearby settlement with a population of 6 by day and 4 by night – the pastor and his family of four and two grain elevator workers who showed up daily for work. The grain elevator sat by a small railroad we called BF&E – Back and Forth Empty – which it mostly was.

No indoor plumbing at my grandparent’s concrete house until 1958 (my sophomore year), the same year President Ike started building the Interstate highway through the state.

Refrigeration was an icebox that literally had a block of ice in the top and, at best, just kept things cool. But if you grow, kill, extract, or fetch most everything you eat on a near-daily basis, you don’t concern yourself much with refrigeration.

Maybe all this is at the root of my mild embarrassment over my riches.

With virtually nothing, they got along just fine. They were happy, God-fearing and dedicated family folks that never harmed a soul and helped many. They did die early, literally worn out – but at peace.

Disposal, after they were gone, didn’t involve anything resembling a 4’x6’ white-on-white unused albatross. In fact, most of their belongings, from what I can recall of them, may well have fit in that same 4’x6’ space.

So, yeah, I guess there’s a life lesson in all this. Don’t we all get there eventually?

It’s just stuff; accumulation and an eventual headache; an unhealthy attachment to the temporal; a keeping up with/ahead of the Joneses; a satisfying of a comparison complex.

Pick your psychic poison!

You’ve heard the cliché “you never see a U-haul behind a hearse”. I’m asking whoever is left of my family, should any outlast my 112.5 years, to violate that “never”. I want a small trailer to back up to my gravesite, tilt-up and slide a few items on top of my coffin: my 1966 Gibson Hummingbird guitar, my 1990-vintage Sage fly rod and my Ping putter. Oh, maybe I would include 200-300 books I’ve read that I guarantee, nobody else would bother with.

Because that’s really what I’d like to move my life to – that simplicity. I recall when my dad died at 81, everything he owned took up only a 12×12 spot in his son-in-law’s airplane hangar. I took from that modest pile his ubiquitous pocket knife, the weather barometer he looked at every day and a handful of antique carpentry tools that he had inherited from his father.

These round out the memory.

So if I ever am tempted to buy another $1,200 4’x6’ name-brand anything, I’ll simply grab Dad’s pocket knife and nick myself with it to return me to sanity and simplicity.

Thanks, Dad, for the simplicity mindset – and the antidote.

Best wishes for 2020!

Thanks for being a loyal subscriber and reader in 2019!

Wishing you the happiest of holiday seasons.

Gary Allen Foster

www.makeagingwork.com

Why Your Free Time In Retirement Doesn’t Feel Right.

What are the chances that the following statement would be found in any of a financial planner’s training manuals?

“Ironically, jobs are actually easier to enjoy than free time, because like flow activities they have built-in goals, feedback rules, and challenges, all of which encourage one to become involved in one’s work, to concentrate and lose oneself in it. Free time, on the other hand, is unstructured, and requires much greater effort to be shaped into something that can be enjoyed.”

This little slice of advice comes from Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (henceforth, for obvious reasons, referred to as Mr. C), considered one of the co-founders of positive psychology and originator of the psychological concept of “flow”, a highly focused mental state conducive to productivity.

When you’ve been hanging out in the self-development world for multiple decades and plowed through several hundred books in that genre as I have, you are bound to bump into Mr. C repeatedly and his concept of “flow”.

In Mr. C’s words, flow is “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it”

He went on to say: “The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

That’s the “flow” mental state.

When he published his book “Flow” in 1990, his findings pushed back against conventional wisdom. That conventional wisdom, which still prevails today, is that relaxation will make us happy. Less work and more leisure are what we want.

Mr. C’s research revealed that we have that wrong. He found that people were happier at work and less happy relaxing than they suspected. The more “flow” experiences a person has in a week or month the higher the person’s life satisfaction.

He takes this perspective further:

“Ironically, jobs are actually easier to enjoy than free time, because like flow activities they have built-in goals, feedback rules, and challenges, all of which encourage one to become involved in one’s work, to concentrate and lose oneself in it. Free time, on the other hand, is unstructured, and requires much greater effort to be shaped into something that can be enjoyed.”

Human beings, it appears, are at their best when engaged deeply in something challenging.

Boredom ahead

As I’ve engaged soon-to-be-retired executives with my retirement coach hat on, many express concern about becoming bored. They know that going from 110 miles an hour to a near full stop isn’t going to work for them. Several post-retirement execs have confirmed that it’s a legitimate concern.

Steve, a newly retired hospital CEO, found his new free time a nice change. But after a year he began to miss some of the challenge, identity, and structure that came with his high-profile management role.

He had no shortage of volunteer activities come his way but found most of them “shallow” in nature, lacking the type of “deep work” he had been accustomed to and that occasionally took him to a flow state.

We talked about a “middle-ground”, finding a project that he valued enough that he could see himself experiencing a taste of the deep work he retired from and balancing it with taking advantage of the new free time. He has a shortlist of projects under consideration.

It occurred to me as I revisited Mr. C’s flow state theory that this is a concept that is non-existent in retirement conversations. Can you imagine a financial planner suggesting to a client that s/he should consider remaining in some level of a “deep work” state while retired?

But then, that’s easy to understand why they wouldn’t. Financial planning was started by insurance salesmen and they are trained to sell products. At the core, their goal is to help people move away from that nasty four-letter word called “work”. I suspect there isn’t much training in psychology, the metaphysical, mind/body, or the understanding of the importance of flow in life satisfaction.

My inference is simple: traditional, vocation-to-vacation retirement takes us away from a proven life-sustaining activity – structured, goals-based, flow-state deep work – and into a world that erroneously links relaxation and shallow work to happiness.

The act of going deep orders the consciousness in a way that makes life worthwhile. Flow generates happiness.

Can We Become Age-agnostic? Do Your Part – Be a “Perennial”.

Image by Mabel Amber from Pixabay

The deeper I get sucked into this vortex of dialog about aging – older vs elder, saging versus aging, retirement versus rewirement, etc., etc., ad nauseum – the more I sense that we are creeping to the edge of an age-agnostic era.

What does that mean? It means that instead of our identity being tied to a number it will be tied to how we choose to pursue our life.

Show of hands: how many of you mid-lifers and beyond would find that refreshing?

Hey, Martha – I just met the coolest guy who retired from managing large medical practices. He’s now working with health clinics in our community to organize activities to get people walking on a regular basis to combat rampant obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

How old is he? I don’t know, Martha – I didn’t think to ask. I suppose he may be 65-ish or more, don’t you imagine? After all, he did say he recently retired. For all I know, he could be 80. I just know he was really charged up about this quest. Why do you need to know his age, Martha?

I’ve talked previously about having the choice to be older for longer or younger for longer as we move into and through the “third age” of life. Older for longer is the conventional perspective, but I believe it is beginning to reverse.

Chris Crowley and Dr. Henry Lodge got on that theme twelve years ago with their highly-transformational book “Younger Next Year” (What? You haven’t read it yet? Oh my!) blazing a trail saying that the lifestyle decisions you make can lift you out of a number-related category, away from the “live short, die long” group and into the “live long, die short” category.

The book’s message is timeless.

Be a Perennial

Gina Pell is an award-winning creative director and tech entrepreneur. In 2016, she coined the term “Perennials” to “define the idea that people may be in their prime much longer, in ways that defy traditional expectation about age.”

Ms. Pell, age 49 at this writing, describes Perennials as people who are:

“- ever-blooming, relevant people of all ages who know what’s happening in the world, stay current with technology and have friends of all ages. We get involved, stay curious, mentor others, and are passionate, compassionate, creative, confident, collaborative, global-minded risk takers.”

That kinda has younger-next-year and younger longer woven through it, don’t ya think?

Here’s a short video of Gina describing Perennials and how she came to coin the term:

How many in your similarly-aged circle of friends and family can you tag as a “perennial”?

Does it fit you?

Do you look at life as a time-line? Are you “so 20th-century” that you look at your birth year as relevant?

But,how could you not, with our cultural bent toward putting people in categories?

One-hundred years ago we had two categories: child-adult. Then demographers, statisticians, sociologists, marketers teamed up and we now have seven age-related categories: newborn, infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adult, middle age, and old age.

But that wasn’t enough. We decided we better break down that last category even further. So now we have four stages of old:

Enough already!!! It’s bad enough that I have bunches of other archaic, irrelevant cultural beliefs that I’m still trying to shed that now I need to be dragging around “middle old” at 77.

The Thief Called “65”

Look at that first category of “old” and where it starts. Yep, that eight-decade old artificial finish line of 65 – the FDR-era irrelevant relic that we just can’t seem to shake.

Maybe we should listen up with Gina and forget the birth year.

Let’s ignore a youth-obsessed culture that says our societal irrelevancy begins in our mid-40’s.

Let’s stop getting wrapped around the axle and anxious about what others might think or say if we’re not retired at 65.

Let’s pay attention to models out there that get it. Like Fred Bartlit, 87-year old Colorado attorney I wrote about earlier who still maintains a robust legal practice, skis the back-bowls at Vail, is a gonzo-weight lifter, just wrote a book about how to avoid frailty, maintains a website providing resources that combat aging and refuses to acknowledge the number on his birth certificate.

Fred is one of many that we can emulate.

Be the one that will set the example that your birth date is irrelevant.

Be that ever-blooming Perennial.

////////////////

Share your thoughts below with a comment – I appreciate your feedback.

Also, if you haven’t, you can subscribe to this weekly article at www.makeagingwork.com. I publish Monday of every week. I’ll send over a free ebook with your subscription: “Achieve Your Full Life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Are You On a Two-tank Journey With a One-tank Mindset?

Image by Hebi B. from Pixabay

Stan is a C-level executive in his late fifties. He’s done well, thriving and progressing in the volatile, high-pressure world of healthcare. Also, like many at his level in this chaotically-evolving industry, his career was recently disrupted when he was laid off, despite a stellar performance record, following the merger of two health systems.

Rather than withdraw and lick his wounds, Stan wisely invested in a career-transition program that equipped him to re-enter the industry at a level very close to what he was when laid-off. His successful re-entry happened in just under six months, about half the amount of time re-entry takes for most execs at his level.

I connected with Stan just as he was wrestling with which of two attractive offers to accept to continue to move his career forward – a situation I consider to be a “high-class problem”.

We fell into a brief conversation about “what’s next” for him after this next gig which led to an exchange about whether or not he had given much, or any, thought to his post-career life.

Not surprisingly, he hadn’t wandered very deep into that misty territory. Right now, it’s still all about survival in an evolving, unpredictable industry and continuing to “accumulate” to prepare for whatever that final stage is supposed to look like.

As I probed with a few questions that work well to penetrate this veneer, I uncovered an angst about this looming life-phase that, understandably, gets easily shoved to the background when faced with having to cover a sizeable mortgage and college tuitions – and, most likely, a “bigger than a bread box” lifestyle.

Stan’s initial response was the typical “I guess we’ll figure it out when we get there”. But as the conversation progressed, he acknowledged that he has had recurring thoughts about what he wanted his life to count for and that it couldn’t simply be wrapped up solely in having been a successful healthcare exec.

When I remind folks like Stan that this post-career third-age could be nearly as long as their career phase, most will pick up on the significance of not entering into it casually and unplanned.

I asked him how he would handle going from 110 miles-an-hour to zero. I sensed that the question turned on some new lights.

I left it there with Stan. He agreed that the two of us need to reconnect in the next few years to continue the conversation.

I love the analogy, so I’m stealing it from Chip Conley and his book “Wisdom at Work”.

Yes, I understand – few of you reading this are, or were, at a C-level. But that doesn’t change the argument that most of us need to be wary of this uncharted, unmapped territory.

You wouldn’t attempt to negotiate Chicago with a map of Des Moines. Yet we’ll enter the third-age on fumes with a one-tank mindset built around an 84-year old lifestyle model.

How many other 84-year old methods or tools do you still have operating in your life?

The more conversations I have with retirees – exec and otherwise – the more it becomes obvious that there is a price paid for winging it into retirement. A big chunk of the price is the loss of the valuable early years of the third-age when energy is still high and the accumulated and transferable skills and experiences have not gone stale.

I’m told that, in Australia, the government has a program called “Long Service Leave” which mandates two months of additional vacation for every ten years of continuous service with an employer. It sets up an opportunity for an extended break before transitioning into the retirement phase.

In the U.S. – well, I’m not holding my breath we will ever see anything similar. Adult life here can “feel a bit like a run-on sentence that goes on too long without some punctuation” in the words of Chip Conley.

We are seeing more kids taking “gap years” after high school or college. But what about adults.

Again, I’ll share Conley’s perspective:

“But why should eighteen- or twenty-two-year-olds be the only ones entitled to some punctuation, when they’ve barely even begun writing the run-on sentence of adult life? What about fully-baked adults who just need a little space to pause, to hit refresh, or to rewire? Luckily, as more and more people are liberating themselves from the three-stage model of life, the idea of a lengthy sabbatical in midlife is gaining currency”.

With that perspective, here’s some advice for any of us contemplating this fuzzy “what’s next”:

I’m in the pilot-phase of a course designed to address these, and other, pre- and early-retirement challenges. It’s working title is “What’s Next? Developing A Post-career Roadmap: Transitioning To a Balanced Lifestyle of Labor, Leisure, and Learning”.

If you would like to know more about this offering, drop me an email to gary@makeagingwork.com for more details.

Living a Regret Free Life

This post was originally published on Booming Encore and republished with permission.

By Susan Williams

Over the last year or so I have talked with many people who shared with me that how they currently were living was not what they really wanted to do.

Whether it was pursuing a different profession that would allow them to be more creative or wanting to help other people more or even a desire to feel that they were making a bigger difference in the world – they all had one thing in common.

They were talking about doing something different but we’re not actually taking steps towards doing anything about it.

It made me wonder – what stops us from pursuing what we say we really want to do?

Here are just a few things that I think can get in the way;

Fear

Fear of failure, fear of what other people would think, fear of changing relationships, fear of not having enough time are just some examples of the fear that can stop someone from making a significant change.

Financial

In some cases – especially changing careers – I think that facing a potential financial impact may sometimes be even a bigger challenge than facing fear.

As we get older to think about changing from a comfortable lifestyle to possibly something less secure can be a real challenge. It may not only affect you – in many cases, it can affect an entire family.

Easier Just to Talk About It

Let’s be honest. It’s easier to just talk about what we would like to do in our lives rather than actually doing anything about it.

If we think about all the people who talk about losing weight, getting more exercise, seeing friends more often – but don’t – this is the same type of thing. It takes time, work, dedication and commitment to actually pursue something new.

Support

To make a significant change can often require support – family, friends, colleagues – especially if your decision could impact others.

So why bother? If we have to get over some of these hurdles is any significant change really worth it?

As I thought about this question, I was reminded of a TED video I watched a while back presented by Kathleen Taylor, a mental health counselor who worked with people in their final days of life.

In her presentation, Kathleen shared what was discovered as the number one regret at the end of a person’s life. She shared the following thought that was voiced by many in their final days;

“I wish I had the courage to live a life true to myself and not the life that others expected of me.”

Based on this, I think the answer to make a change or not make a change is truly a very personal decision.

The “follow your passion” or “pursue your dreams” advice looks great on Facebook and Twitter images but any significant change is a very personal decision with many different facets to consider.

I think the big question is to ask ourselves how we think we will feel at the end of our lives.

Will the choices and decisions that we have made allowed us the opportunity to live the life we really wanted to live?

I think if we can answer this question honestly and have made decisions based on this question then the choices as to whether we decide to undertake a significant change becomes easier.

Our lives will then be something to look back on with both joy and satisfaction – and without any regrets.

Here is the TED Talk given by Kathleen Turner – Rethinking the Bucket List;

Susan Williams is the Founder of Booming Encore – a digital media hub dedicated to providing information and inspiration to help Baby Boomers create and live their very best encore. Being a Boomer herself, Susan loves to discover ways to live life to the fullest. She shares her experiences, observations and opinions on living life after 50 and personally tries to embrace Booming Encore’s philosophy of making sure every day matters. For daily updates to help you live your best encore, be sure to follow Booming Encore on Twitter and join them on Facebook. (Link for website: www.boomingencore.com / Link for Twitter: www.twitter.com/boomingencore and Link for Facebook: www.facebook.com/boomingencore.

On Becoming a “Sage” – A Podcast

I had the good fortune recently to be asked to do a guest interview with Jann Freed, PhD, on her “Becoming a Sage” podcast. Jann is a well-known business consultant specializing in strategic planning, leadership development, and life planning.

You can learn about her and her services at www.leadingwithwisdom.net.

Jann liked my guest post on Next Avenue entitled “Your Second Half Should Be Filled With These Four-letter Words” and asked me if I would be interested in an interview for her monthly podcast.

It was an easy decision to make.

It was particularly flattering to be included amongst the collection of Jann’s podcasts that included such notable names in the field of successful aging and life planning as Marci Alboher, VP, Strategic Communications at Encore.org; Ashton Applewhite, author of the best-seller “This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism“; Chip Conley, AirBnB executive and author of an exciting new book “Wisdom @ Work: The Making of a Modern Elder“; George Schofield, designated a Top 50 Influencer in Aging by Next Avenue and author of “How Do I Get There from Here?: Planning for Retirement When the Old Rules No Longer Apply“, and others.

Jann and I covered a lot of ground. Click on the podcast title below, listen and let me know what you think.

Becoming a Sage: Gary Foster

Thanks for listening.

Older for Longer? Or Younger for Longer? The Choice is Ours.

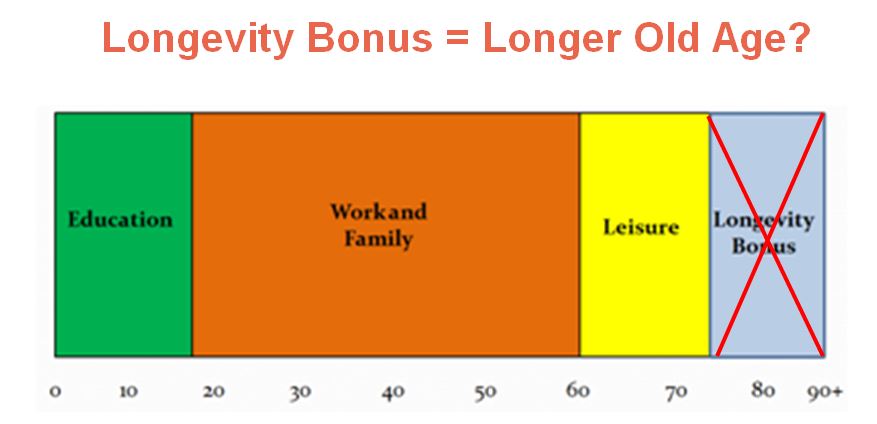

So the prospect of 25-30 more years beyond the average retirement age in the U.S. puts us in a territory we haven’t been in before. And we find ourselves with no roadmaps. Where mom and dad, or granny and grandpa had a few years of bingo, bridge, and bocce ball, we now face the prospect of multiple decades of – what?

Just being older longer? Who wants that? But that’s what happens when there is no plan for this extended longevity.

Well, we’re getting smarter now and discovering that “every day is Saturday” or “I have plenty to keep me busy” is not a healthy plan for this extended longevity period. There is this thing called “boredom” or “stifling sameness” that sets in when every day becomes the same people, place, time, combining to yield the same result.

Mitch Anthony, author of “The New Retirementality”, puts it this way:

“‘Every day is Saturday’ quickly becomes a life of those Mondays you used to dread.”

He goes on to say:

“You need to have realistic expectations regarding retirement. Thinking that going from working full-time to a life that involves focusing on only leisure activities gets old quickly—and makes us older in the process. Most of us will be disappointed once we find out that our vision of retirement is not the nirvana we thought it would be.”

It’s rare that I hear a recent retiree use the word “bored” in describing the current status of their retirement. I get it – who’s going to admit that their retirement isn’t sailing along as presented and expected?

The “no structure” trap

I’ve had lots of conversations over the last year with newly-retired hospital and large medical practice executives. These are highly-educated, highly-compensated folks stepping away from very time- and stress-intensive positions. They created and thrived in a very structured environment – a necessity in an industry which, at its core, is often akin to herding cats and just simply keeping the wheels on because of the ever-changing world of government intervention.

Being busy soon after retirement never seems to be an issue.

But, I’m also hearing that the move from structure to non-structure is wearing thin. Several have expressed a sort of “drifting” or “ping-ponging” nature to their retirement and feeling that “there is more that I can do that has more meaning.”

Steve is a former hospital CEO that is three years into his retirement. He recently shared this with me: “I enjoy being by myself and with my family. But I need intellectual stimulation, a new challenge, something that uses my expertise, experience and leadership abilities.”

He laments that he didn’t give thought to, or have someone to help him with, things to consider post-career – a method for “finding himself” or a path to more purposeful use of his time at this stage.

His financial goals were achieved early. But nowhere in conversations with financial advisors was there any conversation about “what’s next” from a mental, physical, social or spiritual perspective. Nor did anything along the path to retirement “hook” him and steer him toward something that would ignite dormant passions or a greater sense of purpose in how he was living.

Like so many, this very talented, experienced executive walked from a structured environment into an unstructured environment with the assumption that retirement would “take care of itself”.

Steve, at 66, understands he probably has a longer roadway ahead than previous generations. That’s part of his angst, I believe. Perhaps fear of a meaningless, dependent post-career existence. In other words, just being “older longer.”

We’ve agreed to work together and experiment with some techniques to help him get on this “purpose-path” that seems to be simmering in his psyche. It’s interesting to note that, even with his successful career experience and education, he is most interested in starting that process by going all the way back to doing some basic strengths and talent assessments and tests.

With this reminder of how he is “wired up” and some guidance on the development of a flexible, written plan for his post-career life, I believe we will carve out that roadmap that he feels is missing for the remainder of his days.

I am confident that we will see a Steve that is “younger longer” with no fear of being “older longer.” More importantly, I believe, will be a focused transfer of skills and experience back into the marketplace in a way that will allow him to leave a more meaningful footprint.

It’s a discovery path that is an option for all of us if we are willing to stare down that “aging elephant in the room.”

It’s Time to “Take Back and Own” Your Elderhood

How did you react when you received your AARP card just before your fiftieth birthday?

Were you:

Surprised? We probably don’t want to know how much they know about us.

Flattered? Just a thought – you might want to raise the bar.

Excited? You love those weekly Bed Bath and Beyond 20% discount coupons also, don’t you?

Ambivalent? Good choice.

Pissed? Good –I’m not alone.

In one trip to the mailbox, I was slammed, culturally and without my permission, into an insulting, miscast category entitled “elderly”.

I refuse to contribute to this insurance-company-in-disguise.

Yes, it defies all logic that I would pass up a 12% discount on ParkRideFly USA airport parking. Or a 15% discount on Philip Lifeline medical alert service or save on an eye exam at Lenscrafters.

But, I’m sorry. I just haven’t gotten over the insult that arrived twenty-eight years ago with that AARP letter.

I guess that kinda makes me seem like one of those grumpy, crass, hard-headed ol’ farts I swore I’d never become.

I’m working on fixing that.

So it was that when I got a mere one chapter into Chip Conley’s new book “Wisdom at Work” (reference my 10/21/19 article) that I got affirmation that my resistance to that premature elderly tag will have served me well.

If you’ve been hanging around my weekly diatribes for a while, you’ve no doubt detected that I seem to have a new hero every week or so. Well, this week – and I think for a good while longer – it’s Chip Conley.

I wrote two weeks ago about his Modern Elder Academy, a “boutique resort for midlife learning and reflection” and his coining of a new cultural portal he labeled “middlescence”.

My intrigue with his inventiveness motivated me to Amazon Prime his book and dig in.

So glad I did.

I didn’t need to go past Chapter 1 to know that Conley’s is a voice and message that needs to be heard – across generations. He is saying so much more eloquently and authoritatively what I’ve been waltzing and bumbling around with for most of my two years with this blog.

At the heart is the message that it’s time to:

“liberate the ‘elder’ from the word ‘elderly’. ‘Elderly’ refers solely to years lived on the planet. ‘Elder’ refers to what one has done with those years. Many people age without synthesizing wisdom from their experience. But elders reflect on what they’ve learned and incorporate it into the legacy they offer younger generations. The elderly are older and often dependent upon society and, yet, separated from the young.”

Conley reminds us that the average age of someone moving into a nursing home is eighty-one vs sixty-five in the 1950s and that this leaves a lot of people not yet elderly but as elders.

He encourages us to “take back the term elder” and own it as a modern definition of someone with great wisdom especially at a time we need it.

I loved this choice of words:

“Let’s make it a ‘hood’ that’s not scary. Just as a child stares into adulthood with intrigue, wouldn’t it be miraculous if an adult peered into elderhood with excitement?”

Count for me how many, amongst your family, friends, acquaintances, co-workers, that you think will “peer into elderhood with excitement”. I’m guessing you didn’t need the fingers on both hands.

While you are at it, count up the number of millennials and GenX’ers you know (if you know any at all) that are excited about the same thing i.e. about us being anything more than irrelevant “elderlies.” Even fewer fingers, right?

Conley brings a different but refreshing, evidence-based perspective on how and why this all can change; on how generativity can close the gap; on how we need those digi-head millenials as much as they need us wisdom keepers.

It’s time for you and me to become more intentional about our “wisdom worker status” and to redefine our third-age as one of “mature idealism.”

Consider Conley’s perspective on this:

“For many of us, the baseball game of our career will likely go into extra innings. So maybe it’s time to get excited about the fact that most sporting matches get more interesting in the last half or quarter. By the same token, theatergoers sit on the edge of their seat during the last act of a play when everything finally starts to makes sense. And marathon runners get an endorphin high as they reach the final miles of their event. Could it be that life gets more interesting, not less, closer to the end?”

I’ll wrap with these two powerful quotes from the first chapter of Conley’s book.

“If you can cause maturity to become aspirational again, you’ve changed the world”. Ken Dychtwald, Age Wave

“In spite of illness, in spite even of the arch-enemy, sorrow, one can remain alive long past the usual date of disintegration if one is unafraid of change, insatiable in intellectual curiosity, interested in big things, and happy in small ways.” Edith Wharton

Anybody up for joining this “elder revolution” and become Modern Elders? There’s a lot of room.