“Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one’s self-esteem. That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily, and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.”

So says Thomas Szasz, Hungarian-American academic, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst.

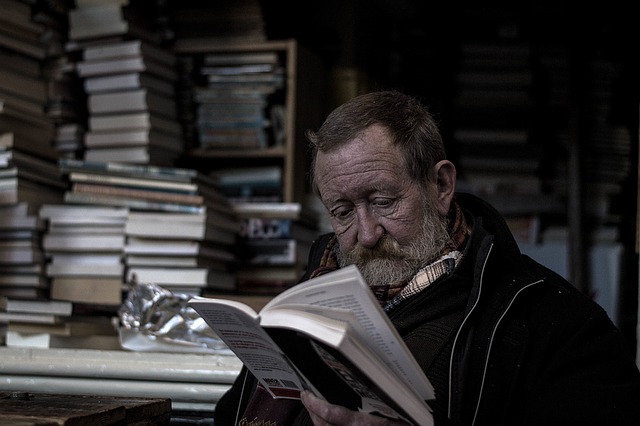

Mr. Szasz’s statement sort of pissed me off. Cannot learn at all? C’mon, I’m learning something new every day at 77.

I’ll bet (I hope) you are too.

I’ll confess, it’s a tad harder. Well, maybe more than a tad. My brain’s CPU seems to be stuck at Windows XP and the hard disk could use a partial download to the cloud to free up some space.

But not at all, Mr.Szasz?

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

They just finished a full-week of drama camp and both had significant roles in the play that wrapped up the week.

My wife and I weren’t able to attend the play. During their visit this week, my wife asked them to do their parts for us.

Our culture hasn’t gotten to them with the “self-importance” thing yet. With these two, you always get a bit more than you bargained for – in energy, enthusiasm, craziness. With this request, they didn’t disappoint.

They did THE WHOLE PLAY for us!!

That’s right – their parts and everybody else’s part. Dances included. And with some of their own improvisation sprinkled in. A full week after the performance.

That same day, I couldn’t, for the life of me, remember a quote I had read earlier that I wanted to capture. Nor could I even remember the book I read it in (I have four books going right now).

So maybe Thomas has a point. But I’m not willing to concede on the “at all” part. I’ll concede on the speed thing, both in learning and retrieving, but not on my ability to continue to learn, and learn deeply.

In fact, since I’ve lost my sense of self-importance (please, don’t cross-check that with my wife), I’m learning at a faster clip and in more volume than I was 20 years ago when I was in the middle of building self-importance in the corporate world.

With titles, position and the opinion of others now in the back seat, I’m highly motivated to continue to learn what I want to learn.

My reading is more focused on my life quest and has shifted to more non-comfort-zone reading. Best selling author, Stephen J. Dubner , author of “Freakonomics” and “Superfreakonomics”, was right when he said: “most ‘important’ books aren’t much fun to read. Most fun books aren’t very important.”

I’ve read several un-fun books this past year and have been stretched in the process.

I’m also trying to write something daily that pushes me outside my comfort zone – like this article.

My Toastmaster Club gives me an opportunity weekly to stretch, test, and refine my speaking skills, both prepared and impromptu.

I wish all this was coming up roses. I will admit to continued frustration with the failure to retain the information I read and with the fits and starts of my progress in both writing and speaking.

After reading over 500 books over the last decade, I confess that I have retained very little of what each book said. I can look at the cover of a book on my “favorites” shelf and honestly not be able to tell you much of what I learned from it that was significant.

When a good friend recommended a book called “Peak. Secrets From the New Science of Expertise” by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool, I did my usual thing – I bought the cheapest used paperback copy on Amazon.

As is often the case, it was a timely injection into my reading stream. I read it in five days of early morning reading time. It is replete with highlights, margin notes, paper-clipped pages and colored tabs protruding from the side that mark the mega-important pages.

It’s the quirky way that I attack books. It’s also why I NEVER lend them out or why I can’t recycle them to a used-book grave because they are such a marked-up mess.

But I’ve been doing that with books forever, and I still can’t remember much of their content.

Ericsson’s book may be the catalyst that will change all of that for me – and perhaps for you if you are experiencing similar frustration with retaining and applying what you’ve learned. Ericsson’s research appears to have the key to unsticking me from a handful of stuck areas in my life – reading retention, writing and speaking with impact, frozen golf handicap, plateaued guitar playing – to name a few in my life.

Ericsson’s extensive research and human experiments on memory retention reinforce the point that, like a computer, our brains have short-term memory (RAM) and long-term memory (hard drive). We’ve known for decades that there is a limit to what our short-term memory will retain. It’s designed to hold small amounts of information for a short time.

That’s why you forget the new neighbor’s name fifteen minutes after you met them unless you do something to move it out of short-term to long-term memory – such as repeating the names over and over again until the transfer takes place.

Our brains have a strict limit on what they can hold in short-term memory. The average limit is seven items, which explains why we have to write ten-digit phone numbers down rather than expect to remember them (it doesn’t get easier as we get older, have you noticed?)

Ericsson’s experiments and research confirmed that, unlike short-term memory, long-term memory doesn’t have an upper limit, but takes much longer to deploy.

He provides examples throughout the book of truly amazing feats of memory to illustrate this quality of our brain. His cornerstone experiment involved working with a bright, young Carnegie Mellon grad student testing his ability to present digits that were read to him at the rate of one per second – too fast to transfer them to his long-term memory. Repeating them back to Ericsson, the student continually hit the wall at number sequences eight or nine digits long.

But, over two years and two hundred training sessions, the student successfully remembered eighty-two digits read to him one per second.

Eighty two!!

He did it by refining a mental process for moving the digits to his long term memory.

Using other examples of exceptional performance throughout the book – blindfolded chess players, record-holding cyclists, typist exceeding 200 words per minute, basketball free-throw shooters – Ericsson concludes that “no matter what field you study, music or sports or chess or something else, the most effective types of practice all follow the same set of general principles.”

It’s not about genetics or innate talent.

Wanna be a “grandmaster?” I know, few of us do because we don’t think we have the “innate talent.” But if we did want grandmaster status, we would have to accept that high achievement is not rooted in intelligence or inborn talent.

It’s rooted in practice, deep deliberate practice.

In Ericsson’s words: “The answer is that the most effective and most powerful types of practice in any field work by harnessing the adaptability of the human body and brain to create, step by step, the ability to do things that were previously not possible” and that “- all truly effective practice techniques work in essentially the same way.”

I had read other similarly-themed books about deliberate practice, the secondary role of talent versus effort, the significance of 10,000 hours to master something (Geoff Colvin’s “Talent Is Overrated”; Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers”, Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code”) and have had the “head knowledge” of what separates the great from the good from the mediocre.

Ericsson’s book caps that little library and is providing a eureka moment that, as I write this, is inspiring me to move what I’ve learned from my head into practical application, starting with forgiving myself for the years of wasted surface-level practice along my vocational path.

My braggadocious posture about reading 75 books a year is now not only embarrassing but also reveals my naivete about meaningful learning. It represented “notches on the gun”. It was get-that-one-on-the-shelf-and-get-on-to-the-next-one, searching for that magic quote, sentence or paragraph that will turn my success ship.

Previously, I would finish every book, even if it wasn’t reaching me. I’m over that. I’ve learned that many books are fluff and a waste – and that not every book has its time and space in my world. If it isn’t reaching me but there is a hint of something valuable, I will now shelve it and maybe come back to it and see if its time has come.

Before, if I finished a book that really reached me, I’d finish and shelve it on my “A” shelf, only occasionally coming back months or years later to reread it. No more of that either. I now stay with the book and try to move as much of the really important content to my long-term memory by rereading the highlights/paper-clipped/colored-tab pages and then (I know this seems nutty!) writing the really, really good stuff on 3x 5 cards to keep in the book.

Those are my cliff notes for further review down the road.

Four levels of practice.

Reflecting on “Peak”, it is clear that we can choose the level of expertise or mastery that we want, independent of innate talent. Colvin, Gladwell, and Coyle also said that in their books.

And we can do it at any age, even as a third-ager.

We have four practice choices as we move forward in life:

- No practice

- Practice

- Purposeful practice

- Deliberate practice

No practice

This is the default and where many of us end up. Accepting our fate; maintaining the comfort of the status-quo; conceding to our inherent laziness; not understanding how our brain/body works at its best; being goalless, drifting and led, not leading. Then we hit the death bed and express regrets for never having taken any risks – or worked hard at getting good at something worthwhile.

Practice

This is “naïve practice” which is essentially just doing something repeatedly and “expecting that the repetition alone will improve one’s performance”, according to Ericsson. It’s practice without clear goals, no feedback mechanism, no stretch. This too is comfort-zone territory.

This is me for the last twenty years on the driving range with $7 buckets of balls hitting them with no sense of what needs to be fixed, no one to give me feedback on why most are mishits, deepening the defects in my swing and making it harder for a coach to coach them out of me.

It’s “doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results” defined by Einstein as “insanity”. That shows up often in my guitar playing where I sit and entertain myself by playing stuff I already know well and not pushing myself to add a new tune, technique, new rift, or extending my hand stretch.

It’s doing a sales call using the same script/pitch over and over and wondering why prospects aren’t converting and thinking that “they” will eventually get smart and change if you just stick with it long enough.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

Purposeful practice

In contrast, purposeful practice is more purposeful and focused. According to Ericsson and Poole, purposeful practice has the following characteristics:

- Purposeful practice has well-defined, specific goals. Without this, there is no way to judge whether the practice session has been a success. Permit me to give you an example from my own life.

I love golf. My 22 handicap has not moved in ten years. The last few years, I’ve been tracking several components of my game: fairways hit, greens-in-regulation, chips/pitches, putts. The glaring deficiency in my game is greens-in-regulation – my ball is invariably on the green one or more shots more than it should be to make par. I average a paltry two G-I-R’s per eighteen-hole round. No magic here. My approach shots stink, meaning that’s where my problem lies.

I’m setting the goal for this season of an average of six G-I-Rs and a handicap of 18. I’ve already taken lessons from a pro and know what to do – learn to make a freaking approach shot!

- Purposeful practice is focused. I know I have virtually no chance to change my handicap or G-I-R unless I focus my attention and effort on that missing component of poor approach shots. So my practice is focused on improving that shot selection.

- Purposeful practice involves feedback. You have to know what you are doing wrong. That’s where the golf pro comes in. He can watch a few swings and know what needs to change and instruct me accordingly. I have also enlisted the help of my weekly playing partner on what to watch for in my swing and to let me know when I’m doing it wrong.

- Purposeful practice requires getting out of one’s comfort zone. This may be the most important part of purposeful practice, according to Ericsson. It’s a fundamental truth about any kind of practice: if you don’t push yourself beyond your comfort zone, you will never improve. “Try harder” should give way to “try different.”

Deliberate practice

Most of us would do well to get from “naïve” practice to purposeful practice. That move alone can produce amazing results.

But there is yet another level of practice, according to Ericsson, that is the “Gold Standard”. It’s called deliberate practice – it’s purposeful practice on steroids.

Here are a couple of examples:

- It’s Tiger Woods dropping 20 golf balls into a sand trap and stepping on each one before he hits it out.

- It’s the planet’s best acoustic guitar player, Tommy Emmanuel, committed to “being better tomorrow than I am today” and learning a new tune or rift every day, or working with another artist in a different music genre as often as he can. In his sixties, he performs 300 days a year around the world.

- It’s my first jazz guitar teacher in the mid-sixties who looked at my self-taught technique and said “we’re starting over.” He stuck me into a violin book for weeks to teach me the fretboard and to correct a dismal right-hand technique before we even started a dialog about playing jazz guitar. It was miserable, boring practice that had the most profound impact on my playing for the next five decades.

Here’s what I learned from “Peak” about “deliberate practice” and how I will be applying it:

- Develop clear mental representations (visualization) of what I want to accomplish.

- Narrow, refine and make my five-year goals more specific

- Develop baby-steps toward each five-year goal

- Get more focused, eliminate the distractions that rob from full attention (can you spell “smartphone” and “Facebook”?)

- Expand my sources of feedback – find out from others if I’m doing things right. (Many thanks to those of you who have been sending me comments on my blog – I take them seriously)

- Get out of my comfort zone. “Trying harder” will now become “try different”.

- Involve coaches – both live and virtual

- Be consistent – write daily, publish weekly

- Be kind to me and patient with the speed of development

It’s revelatory to track the path followed by some of the world’s greatest achievers and learn that “prodigy”, “innate talent”, “genius” rarely applies. Time and practice mark the path of high achievers.

And that they don’t stop learning as they age.

So Mr.Szasz, with all due respect, I’ll keep learning – because I can. And I must. My string, and that of my compatriots in this “older person” category hasn’t run out. If we’ve stopped learning, we’ve made one of the most unfortunate mistakes we can make if we wish to live a longer, healthier life.

Your thoughts are welcome – please scroll down and leave a comment.

that spoke to how we have, with the help of creative social scientists and enterprising capitalists, expanded from two cultural portals 150 years ago (childhood – adulthood) to seven today (newborn, infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adult, middle age, and old age).

that spoke to how we have, with the help of creative social scientists and enterprising capitalists, expanded from two cultural portals 150 years ago (childhood – adulthood) to seven today (newborn, infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adult, middle age, and old age). I’m a late-stage septuagenarian with a middlescence mindset. Without it, I haven’t got a prayer of getting to my target of living to 112 ½.

I’m a late-stage septuagenarian with a middlescence mindset. Without it, I haven’t got a prayer of getting to my target of living to 112 ½.

It’s discouraging, with our awareness of the devastating impact of the disease, that virtually no progress has been made in finding a cure or treatment, despite billions poured into research. It seems to be a classic case of trying to catch a racehorse after it has left the barn.

It’s discouraging, with our awareness of the devastating impact of the disease, that virtually no progress has been made in finding a cure or treatment, despite billions poured into research. It seems to be a classic case of trying to catch a racehorse after it has left the barn.

One of the most vocal critics of our food system is physician Dr. Michael Greger of

One of the most vocal critics of our food system is physician Dr. Michael Greger of  The only way to increase the amount they get naturally is by getting our heart rate up.

The only way to increase the amount they get naturally is by getting our heart rate up. I hope you’ll take this seriously. None of us want to end up that stooped, shuffling old person. I get it – exercise, especially strength training, is inconvenient, usually painful starting out and you won’t feel like the in-crowd at the local fitness shop or rec center. But without the strength-training component, we face

I hope you’ll take this seriously. None of us want to end up that stooped, shuffling old person. I get it – exercise, especially strength training, is inconvenient, usually painful starting out and you won’t feel like the in-crowd at the local fitness shop or rec center. But without the strength-training component, we face

“In a world that is constantly changing, there is no one subject or set of subjects that will serve you for the foreseeable future, let alone for the rest of your life. The most important skill to acquire now is learning how to learn” John Naisbitt

“In a world that is constantly changing, there is no one subject or set of subjects that will serve you for the foreseeable future, let alone for the rest of your life. The most important skill to acquire now is learning how to learn” John Naisbitt

But one thing is certain. Like anything else, if I don’t set the goal, I for sure won’t get there. So what if I miss it by 5 or 10 years? It beats buying into only living to the average U.S.male lifespan of 78.69 years. Especially when you are 77.5, which I am.

But one thing is certain. Like anything else, if I don’t set the goal, I for sure won’t get there. So what if I miss it by 5 or 10 years? It beats buying into only living to the average U.S.male lifespan of 78.69 years. Especially when you are 77.5, which I am.

Culturally, we’ve been taught to wind down as we age, to come in for a landing after several decades of flying high. A mindset that suggests another take-off and moving into a future that could be bigger than a high-achieving past is foreign to us when, in fact, we are in an ideal position to make our future bigger. Maybe not in title; maybe not in money; maybe not in culturally-perceived prestige. But we can bring and pay forward our talents and acquired skills and experiences to serve others in transformational ways that exceeded what we did in our past.

Culturally, we’ve been taught to wind down as we age, to come in for a landing after several decades of flying high. A mindset that suggests another take-off and moving into a future that could be bigger than a high-achieving past is foreign to us when, in fact, we are in an ideal position to make our future bigger. Maybe not in title; maybe not in money; maybe not in culturally-perceived prestige. But we can bring and pay forward our talents and acquired skills and experiences to serve others in transformational ways that exceeded what we did in our past.

So why am I sounding an alarm here?

So why am I sounding an alarm here? interact/interface/intertwine? Do you know the key biomarkers of your health and where yours are? How conscious are you of the insidious nature, positive and negative, of your current habits and the role they play in your long-term health? We exist inside of a 24×7 immune system of 35 trillion cells that are working hard to keep us healthy despite how we ignore and mistreat them. The knowledge to know how to provide them what they need to do their jobs has existed for a long time, but we give it up to complacency and convenience. That is, until a calamity hits.

interact/interface/intertwine? Do you know the key biomarkers of your health and where yours are? How conscious are you of the insidious nature, positive and negative, of your current habits and the role they play in your long-term health? We exist inside of a 24×7 immune system of 35 trillion cells that are working hard to keep us healthy despite how we ignore and mistreat them. The knowledge to know how to provide them what they need to do their jobs has existed for a long time, but we give it up to complacency and convenience. That is, until a calamity hits. P.S. You might get pushback from your doc. Here’s why: what you are asking of them doesn’t fit the corporate model that they have stepped into if they are part of a large health system or large consolidated practice. Expectations on the part of the system or practice are to see as many patients a day as possible. Follow the money. The more visits, the more insurance payouts. Someone like you with your questions and requests take time that your doc may want to take with you but be forced to avoid because of insurance restrictions and health system expectations. Plus a lot of what you will want to know and discuss doesn’t translate into the boxes in the electronic medical record that your doc has his nose in throughout your entire meeting. You are creating more “paperwork” for an already overburdened doc. It’s your health – don’t let all that get in the way.

P.S. You might get pushback from your doc. Here’s why: what you are asking of them doesn’t fit the corporate model that they have stepped into if they are part of a large health system or large consolidated practice. Expectations on the part of the system or practice are to see as many patients a day as possible. Follow the money. The more visits, the more insurance payouts. Someone like you with your questions and requests take time that your doc may want to take with you but be forced to avoid because of insurance restrictions and health system expectations. Plus a lot of what you will want to know and discuss doesn’t translate into the boxes in the electronic medical record that your doc has his nose in throughout your entire meeting. You are creating more “paperwork” for an already overburdened doc. It’s your health – don’t let all that get in the way.

are being published each year worldwide – well, my sanity is up for question.

are being published each year worldwide – well, my sanity is up for question.

Have any of them expressed concern or interest in the current destruction and burning of the lungs of our planet to graze more four-legged saturated-fat-factories?

Have any of them expressed concern or interest in the current destruction and burning of the lungs of our planet to graze more four-legged saturated-fat-factories?

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

I use my personal journey in my coaching. I’m admittedly a bit strange in how I view my life calendar. Some time ago, in my 50s, I began to feel the calendar squeezing in – that realization that there may be more days behind than ahead. I was feeling like I was in August, maybe even September.

I use my personal journey in my coaching. I’m admittedly a bit strange in how I view my life calendar. Some time ago, in my 50s, I began to feel the calendar squeezing in – that realization that there may be more days behind than ahead. I was feeling like I was in August, maybe even September.