Why Did Isocrates Live to 98 and We Can’t Make It Past 80? A Longevity Lesson from the Ancient Greeks.

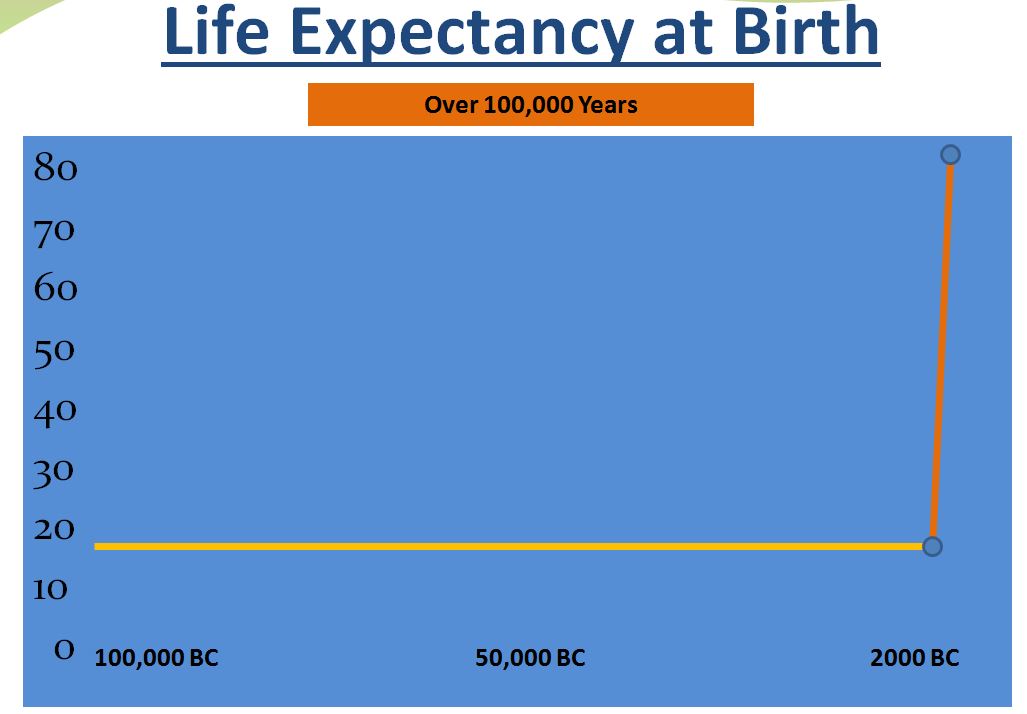

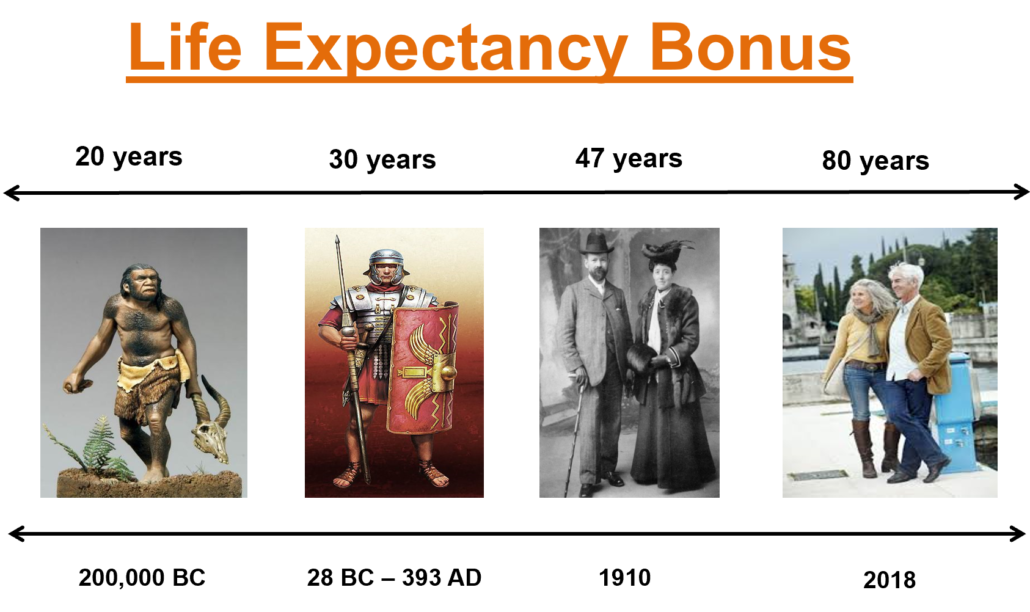

Much has been said about the meteoric increase in average lifespan over the last century. I’ve made a pretty big deal of it all in past articles. Considering that we moved that needle from 47 years to about 80 between 1910 and 2010, I guess it’s worth a mention. Especially since we hockey-sticked it more in 100 years than in the last 100-200,000 years.

The emperor has clothes but they have worn pretty thin.

It makes for a great story, this hockey stick stat. That is until we pull back the curtain and find the glitter has left the gold.

Kudos are due to the medical establishment, government, and technology for teaming up to reverse the elements that resulted in a 47-year average life span. Together they:

- Reversed infant mortality

- Eliminated or radically reduced infectious diseases

- Improved workplace safety

- Improved our drinking water

- Improved quality and availability of food

- Improved education

A lot of “fixing.” A lot of “curing.” A lot of “downstream repair.”

All low-hanging fruit.

Then we hit a wall around 2010 and started going backward.

Now we’re stuck – with institutions that can’t, or won’t, think like the Greeks!

The ancient Greeks probably would have cautioned us to think deeper during that 1910-2010 sprint.

Hygeia vs Panacea

The Greeks, 2,500 years ago, had it right in many areas, but particularly when it came to good health. They identified that medicine had two components – Hygeia and Panacea.

Hygeia equals health preservation and Panacea equals repair. Hygeia equals prevention. Panacea equals cure.

For the Greeks, Hygeia held precedence.

Our 100 years of fixing and repair never got us to that model. We’ve moved far from it with limited interest in moving in that direction.

And the consequences are glaring.

We are getting sicker as a population each day – and have been for the better part of 50 years.

Hygeia and Eugeria

In his outstanding book “Boundless Potential: Transform Your Brain, Unleash Your Talents, Reinvent Your Work in Midlife and Beyond,” author Mark S. Walton reveals a number of things that we (and our medical establishment) can learn from the Greeks when it comes to our health and longevity.

Many of Greek fame lived longer than most. At a time when the normal lifespan was around 35, many of the notable, quotable Greeks lived longer and aged happily.

Walton points out that a study by the Royal Society of Medicine in London explored this in 1994 and 2007, studying the “men of intellectual excellence and achievement” during that period. They found that the “men of fame” had a mean and median life span of 71.3 and 70 years, respectively. Twice the average!

It turns out that the Greeks had another arrow in their quiver of equal importance to hygeia – a term for attaining genuine happiness called eugeria.

According to Walton, eugeria required:

“-a lifelong pursuit of worthy goals through the three components of our humanity: body, mind, and soul.”

Walton examines the Greek eugeria formula and its components:

- They played hard. They were “the first people in the world to play and they played on a grand scale.” Games, athletic contests of every description. Not as an end in itself but as preparation “for the work yet to come.”

- They worked hard. As the world’s first knowledge workers, they never stopped exerting their minds and were the original reinventing people. Knowledge work was the ultimate fun.

- They paid it forward. For them, “-it was clear that the soulful pursuit of paying it forward, of working for the benefit of each other and future generations, provided the greatest payback of all.”

He reminds us that the word philanthropy was derived from two Greek roots: philo (love) and anthropos (mankind) and that:

“The lifelong pursuit of excellence (arete), with the goal of contributing our accomplishments to others – this, to the Greeks, was the ultimate formula, the blueprint, for eugeria, a long and happy life.”

Plato lived to 80; Isocrates to 98; Sophocles to 90; Aristarchus, Democritus, and Gorgias all lived past 100.

Today, you will be front-page media fodder for living 20% past the average life span i.e. to 100. In ancient Greece, living 2x the average or more wasn’t all that unusual.

Walton provides a nice summary:

“While the Athenian paradigm has faded into history, the thinking behind it has endured through the ages – most especially its soulful tenet: that paying it forward, working for the sake of others, pays us back in unexpected ways.”

Our lifestyles, built around bad diet, sedentary living, seeking comfort and convenience, and an increasing lack of generativity would have been unsettling to the Greeks but it’s how we choose to live and thus pull up short of our full life potential.

We won’t get help from a healthcare system that grew up “fixing” and can’t/won’t move off a business model based on cure and a “downstream” mindset that avoids addressing the cause in favor of fixing the symptoms.

The Greeks believed in prevention. Our systems are geared to cure. The Greeks planned “upstream”; we react “downstream.”

The Greeks never stopped learning. We warehouse our brains at a certain age.

And-

-the Greeks had no inkling of the concept of retirement.

I suspect they would have found the concept foolish, maybe even offensive.

We’ve got a lot to learn. The Greeks can still teach us.

The question is: Are we willing to be taught?

What do you think about this? Leave us your thoughts with a comment below. We appreciate your feedback.