“Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one’s self-esteem. That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily, and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.”

So says Thomas Szasz, Hungarian-American academic, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst.

Mr. Szasz’s statement sort of pissed me off. Cannot learn at all? C’mon, I’m learning something new every day at 77.

I’ll bet (I hope) you are too.

I’ll confess, it’s a tad harder. Well, maybe more than a tad. My brain’s CPU seems to be stuck at Windows XP and the hard disk could use a partial download to the cloud to free up some space.

But not at all, Mr.Szasz?

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

My nine-year-old granddaughter and her six-year-old brother this week seemed to fuel Szasz’s argument.

They just finished a full-week of drama camp and both had significant roles in the play that wrapped up the week.

My wife and I weren’t able to attend the play. During their visit this week, my wife asked them to do their parts for us.

Our culture hasn’t gotten to them with the “self-importance” thing yet. With these two, you always get a bit more than you bargained for – in energy, enthusiasm, craziness. With this request, they didn’t disappoint.

They did THE WHOLE PLAY for us!!

That’s right – their parts and everybody else’s part. Dances included. And with some of their own improvisation sprinkled in. A full week after the performance.

That same day, I couldn’t, for the life of me, remember a quote I had read earlier that I wanted to capture. Nor could I even remember the book I read it in (I have four books going right now).

So maybe Thomas has a point. But I’m not willing to concede on the “at all” part. I’ll concede on the speed thing, both in learning and retrieving, but not on my ability to continue to learn, and learn deeply.

In fact, since I’ve lost my sense of self-importance (please, don’t cross-check that with my wife), I’m learning at a faster clip and in more volume than I was 20 years ago when I was in the middle of building self-importance in the corporate world.

With titles, position and the opinion of others now in the back seat, I’m highly motivated to continue to learn what I want to learn.

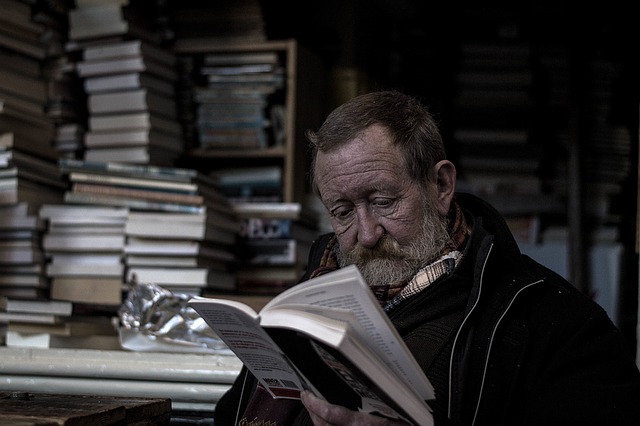

My reading is more focused on my life quest and has shifted to more non-comfort-zone reading. Best selling author, Stephen J. Dubner , author of “Freakonomics” and “Superfreakonomics”, was right when he said: “most ‘important’ books aren’t much fun to read. Most fun books aren’t very important.”

I’ve read several un-fun books this past year and have been stretched in the process.

I’m also trying to write something daily that pushes me outside my comfort zone – like this article.

My Toastmaster Club gives me an opportunity weekly to stretch, test, and refine my speaking skills, both prepared and impromptu.

I wish all this was coming up roses. I will admit to continued frustration with the failure to retain the information I read and with the fits and starts of my progress in both writing and speaking.

After reading over 500 books over the last decade, I confess that I have retained very little of what each book said. I can look at the cover of a book on my “favorites” shelf and honestly not be able to tell you much of what I learned from it that was significant.

When a good friend recommended a book called “Peak. Secrets From the New Science of Expertise” by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool, I did my usual thing – I bought the cheapest used paperback copy on Amazon.

As is often the case, it was a timely injection into my reading stream. I read it in five days of early morning reading time. It is replete with highlights, margin notes, paper-clipped pages and colored tabs protruding from the side that mark the mega-important pages.

It’s the quirky way that I attack books. It’s also why I NEVER lend them out or why I can’t recycle them to a used-book grave because they are such a marked-up mess.

But I’ve been doing that with books forever, and I still can’t remember much of their content.

Ericsson’s book may be the catalyst that will change all of that for me – and perhaps for you if you are experiencing similar frustration with retaining and applying what you’ve learned. Ericsson’s research appears to have the key to unsticking me from a handful of stuck areas in my life – reading retention, writing and speaking with impact, frozen golf handicap, plateaued guitar playing – to name a few in my life.

Ericsson’s extensive research and human experiments on memory retention reinforce the point that, like a computer, our brains have short-term memory (RAM) and long-term memory (hard drive). We’ve known for decades that there is a limit to what our short-term memory will retain. It’s designed to hold small amounts of information for a short time.

That’s why you forget the new neighbor’s name fifteen minutes after you met them unless you do something to move it out of short-term to long-term memory – such as repeating the names over and over again until the transfer takes place.

Our brains have a strict limit on what they can hold in short-term memory. The average limit is seven items, which explains why we have to write ten-digit phone numbers down rather than expect to remember them (it doesn’t get easier as we get older, have you noticed?)

Ericsson’s experiments and research confirmed that, unlike short-term memory, long-term memory doesn’t have an upper limit, but takes much longer to deploy.

He provides examples throughout the book of truly amazing feats of memory to illustrate this quality of our brain. His cornerstone experiment involved working with a bright, young Carnegie Mellon grad student testing his ability to present digits that were read to him at the rate of one per second – too fast to transfer them to his long-term memory. Repeating them back to Ericsson, the student continually hit the wall at number sequences eight or nine digits long.

But, over two years and two hundred training sessions, the student successfully remembered eighty-two digits read to him one per second.

Eighty two!!

He did it by refining a mental process for moving the digits to his long term memory.

Using other examples of exceptional performance throughout the book – blindfolded chess players, record-holding cyclists, typist exceeding 200 words per minute, basketball free-throw shooters – Ericsson concludes that “no matter what field you study, music or sports or chess or something else, the most effective types of practice all follow the same set of general principles.”

It’s not about genetics or innate talent.

Wanna be a “grandmaster?” I know, few of us do because we don’t think we have the “innate talent.” But if we did want grandmaster status, we would have to accept that high achievement is not rooted in intelligence or inborn talent.

It’s rooted in practice, deep deliberate practice.

In Ericsson’s words: “The answer is that the most effective and most powerful types of practice in any field work by harnessing the adaptability of the human body and brain to create, step by step, the ability to do things that were previously not possible” and that “- all truly effective practice techniques work in essentially the same way.”

I had read other similarly-themed books about deliberate practice, the secondary role of talent versus effort, the significance of 10,000 hours to master something (Geoff Colvin’s “Talent Is Overrated”; Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers”, Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code”) and have had the “head knowledge” of what separates the great from the good from the mediocre.

Ericsson’s book caps that little library and is providing a eureka moment that, as I write this, is inspiring me to move what I’ve learned from my head into practical application, starting with forgiving myself for the years of wasted surface-level practice along my vocational path.

My braggadocious posture about reading 75 books a year is now not only embarrassing but also reveals my naivete about meaningful learning. It represented “notches on the gun”. It was get-that-one-on-the-shelf-and-get-on-to-the-next-one, searching for that magic quote, sentence or paragraph that will turn my success ship.

Previously, I would finish every book, even if it wasn’t reaching me. I’m over that. I’ve learned that many books are fluff and a waste – and that not every book has its time and space in my world. If it isn’t reaching me but there is a hint of something valuable, I will now shelve it and maybe come back to it and see if its time has come.

Before, if I finished a book that really reached me, I’d finish and shelve it on my “A” shelf, only occasionally coming back months or years later to reread it. No more of that either. I now stay with the book and try to move as much of the really important content to my long-term memory by rereading the highlights/paper-clipped/colored-tab pages and then (I know this seems nutty!) writing the really, really good stuff on 3x 5 cards to keep in the book.

Those are my cliff notes for further review down the road.

Four levels of practice.

Reflecting on “Peak”, it is clear that we can choose the level of expertise or mastery that we want, independent of innate talent. Colvin, Gladwell, and Coyle also said that in their books.

And we can do it at any age, even as a third-ager.

We have four practice choices as we move forward in life:

- No practice

- Practice

- Purposeful practice

- Deliberate practice

No practice

This is the default and where many of us end up. Accepting our fate; maintaining the comfort of the status-quo; conceding to our inherent laziness; not understanding how our brain/body works at its best; being goalless, drifting and led, not leading. Then we hit the death bed and express regrets for never having taken any risks – or worked hard at getting good at something worthwhile.

Practice

This is “naïve practice” which is essentially just doing something repeatedly and “expecting that the repetition alone will improve one’s performance”, according to Ericsson. It’s practice without clear goals, no feedback mechanism, no stretch. This too is comfort-zone territory.

This is me for the last twenty years on the driving range with $7 buckets of balls hitting them with no sense of what needs to be fixed, no one to give me feedback on why most are mishits, deepening the defects in my swing and making it harder for a coach to coach them out of me.

It’s “doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results” defined by Einstein as “insanity”. That shows up often in my guitar playing where I sit and entertain myself by playing stuff I already know well and not pushing myself to add a new tune, technique, new rift, or extending my hand stretch.

It’s doing a sales call using the same script/pitch over and over and wondering why prospects aren’t converting and thinking that “they” will eventually get smart and change if you just stick with it long enough.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

My instincts and the immutable Pareto Principle of life tell me that 80% of us fit in these two categories.

Purposeful practice

In contrast, purposeful practice is more purposeful and focused. According to Ericsson and Poole, purposeful practice has the following characteristics:

- Purposeful practice has well-defined, specific goals. Without this, there is no way to judge whether the practice session has been a success. Permit me to give you an example from my own life.

I love golf. My 22 handicap has not moved in ten years. The last few years, I’ve been tracking several components of my game: fairways hit, greens-in-regulation, chips/pitches, putts. The glaring deficiency in my game is greens-in-regulation – my ball is invariably on the green one or more shots more than it should be to make par. I average a paltry two G-I-R’s per eighteen-hole round. No magic here. My approach shots stink, meaning that’s where my problem lies.

I’m setting the goal for this season of an average of six G-I-Rs and a handicap of 18. I’ve already taken lessons from a pro and know what to do – learn to make a freaking approach shot!

- Purposeful practice is focused. I know I have virtually no chance to change my handicap or G-I-R unless I focus my attention and effort on that missing component of poor approach shots. So my practice is focused on improving that shot selection.

- Purposeful practice involves feedback. You have to know what you are doing wrong. That’s where the golf pro comes in. He can watch a few swings and know what needs to change and instruct me accordingly. I have also enlisted the help of my weekly playing partner on what to watch for in my swing and to let me know when I’m doing it wrong.

- Purposeful practice requires getting out of one’s comfort zone. This may be the most important part of purposeful practice, according to Ericsson. It’s a fundamental truth about any kind of practice: if you don’t push yourself beyond your comfort zone, you will never improve. “Try harder” should give way to “try different.”

Deliberate practice

Most of us would do well to get from “naïve” practice to purposeful practice. That move alone can produce amazing results.

But there is yet another level of practice, according to Ericsson, that is the “Gold Standard”. It’s called deliberate practice – it’s purposeful practice on steroids.

Here are a couple of examples:

- It’s Tiger Woods dropping 20 golf balls into a sand trap and stepping on each one before he hits it out.

- It’s the planet’s best acoustic guitar player, Tommy Emmanuel, committed to “being better tomorrow than I am today” and learning a new tune or rift every day, or working with another artist in a different music genre as often as he can. In his sixties, he performs 300 days a year around the world.

- It’s my first jazz guitar teacher in the mid-sixties who looked at my self-taught technique and said “we’re starting over.” He stuck me into a violin book for weeks to teach me the fretboard and to correct a dismal right-hand technique before we even started a dialog about playing jazz guitar. It was miserable, boring practice that had the most profound impact on my playing for the next five decades.

Here’s what I learned from “Peak” about “deliberate practice” and how I will be applying it:

- Develop clear mental representations (visualization) of what I want to accomplish.

- Narrow, refine and make my five-year goals more specific

- Develop baby-steps toward each five-year goal

- Get more focused, eliminate the distractions that rob from full attention (can you spell “smartphone” and “Facebook”?)

- Expand my sources of feedback – find out from others if I’m doing things right. (Many thanks to those of you who have been sending me comments on my blog – I take them seriously)

- Get out of my comfort zone. “Trying harder” will now become “try different”.

- Involve coaches – both live and virtual

- Be consistent – write daily, publish weekly

- Be kind to me and patient with the speed of development

It’s revelatory to track the path followed by some of the world’s greatest achievers and learn that “prodigy”, “innate talent”, “genius” rarely applies. Time and practice mark the path of high achievers.

And that they don’t stop learning as they age.

So Mr.Szasz, with all due respect, I’ll keep learning – because I can. And I must. My string, and that of my compatriots in this “older person” category hasn’t run out. If we’ve stopped learning, we’ve made one of the most unfortunate mistakes we can make if we wish to live a longer, healthier life.

Your thoughts are welcome – please scroll down and leave a comment.

Retirement, the First Law of Physics, and the Iron Oxide Risk

Isaac Newton was a great physicist. Maybe not by today’s standards, but he helped us move forward with some pretty big leaps back in his day. Like (1) deciphering gravity; (2) inventing calculus; (3) building the telescope.

He also introduced the “First Law of Physics”.

This law is sometimes referred to as the law of inertia and is often stated as:

An object at rest stays at rest and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force.

The word “object” in the law would seem to reference a solid, physical object – like a rock, a car, a rocket ship, a human body.

I’ll bet, however, that you know a mind or two at rest that is impervious to any opposing view or unbalancing force. I’ve encountered a few. There seems to be quite a collection gathering daily along the Potomac.

Isaac’s law pits inertia against action.

My body and mind seem to favor the inertia and resist the action. Like daily. It’s so much easier, it seems, to be comfortable, inert.

Be honest. You’ve been there.

I found myself thinking about the phases – or portals if you will – that we pass through in life and the “unbalancing forces” that move us through those portals, countering our tendency to be a perpetual “object at rest”. Parents, peers, professors, cultural expectations/pressures. Sometimes it takes a crisis or a calamity before an inertia-beset mind and body get moving.

Psychologists and marketers have brought us to where we now have seven life portals (P.S. 150 years ago, we had two: childhood and adulthood). Each portal (newborn – infancy – childhood – adolescence – young adult – middle age – old age) has inertia and an unbalancing force to counter the inertia.

Aren’t you grateful you had some unbalancing forces in your life that moved you off your inertia-inclined butt at each phase?

Intentional inertia

Speaking of “intentional inertia”, as I scanned those life portals reminiscing on who and what the unbalancing forces were at each phase, it struck me that there is a phase where, culturally, we work somewhat feverishly to establish intentional inertia. Between portal six and seven, middle age and old age.

It’s called (drum roll) – retirement.

Think about it. We’re taking a body in motion, some fast, some slow, some half-fast (sorry – old, tired joke) and we’re suggesting a return to inertia, or at least a measure of it.

We’re entitled to it, we’re told. We’ve succumbed enough to the “unbalancing forces” in the earlier portals. Time to stiff-arm those and experience a little or a lot of good ‘ol inertia.

Funny thing about inertia. This may sound crazy, but my screwy mind went to my days spent on my grandfather’s and uncle’s farms. Both farms had lots of “retired” farm equipment – tractors, combines, plows, various farm implements. What did they do with them? There was no convenient way to “recycle” in those days so they became inert, often at the spot where they quit working.

From there, nature’s payoff for inertia took over – rust. Useless, inert, just taking up space and using up oxygen and moisture to form iron oxide. It’s the sort of “farm junk” that you will see as you drive by any small farm in America.

I know some retirees that remind me of one of my Uncle Ray’s old retired Farmall tractors. Taking up space, using oxygen, immobile and inert.

I’ll bet you know some too.

Between portal six and seven, which I refer to as our “third age”, there is great opportunity for self-imposed inertia.

Our financial planning industry, founded by insurance salespeople a half-century ago, has been hugely successful in convincing us that it’s a time to “wind down”, a time for a “landing”.

No more “take-offs” – you’re done with that.

How could a $60.4 billion industry that’s growing at a 5% pace annually with over 300,000 financial advisors possibly be dispensing bad advice?

Well, it’s really in the eye of the beholder. It’s easy to think inertia when you are burned out doing something you didn’t fully enjoy so you could accumulate the cash to maybe do what you really wanted to do all along and then discover out you don’t have the motivation or the energy to do it. All the while, your financial advisor is in your ear convincing you that there are “golden years” ahead and you deserve them.

Forget this striving business, they say – you’ve paid your dues.

I know it’s a hard truth, but you’ve been relinquishing a good chunk of your net worth to get a lesson in how to form iron oxide.

The word “work” for a mid-to-late-lifer seems to have become a bad word. Something to get away from because, well, just because that’s the way it’s now done. We’ve been hearing that mantra for six or seven decades so it’s not surprising that it’s not going to be dislodged any time soon.

But I see a glimmer of rational thought emerging. There are those amongst the pre-boomer, boomer, and early GenX’ers that are questioning this iron oxide option.

I’m not prepared to call it a full-on revolution yet, but something’s fermenting. If you’ve read this far, you might be part of that fermentation. I hope so.

I hope you literally get pi**** off about the prevailing negative cultural attitudes toward those beyond 55 or 60 and mount your own personal campaign against the forces that encourage us to succumb to Uncle Isaac’s “First Law of Physics”.

Let me know what you think about all this with a comment below. Also, you can subscribe to our weekly newsletter at www.makeagingwork.com and receive a free e-book “Achieving Your Full-life Potential” as a thank you.

Be Part of the “Modern Elder” Movement

Photo by Esther Ann on Unsplash

A couple of years ago, while one with my now-deceased iPod Classic during a workout, I listened to a very stimulating podcast interview with Chip Conley, who, at the time, was a few years into an executive management position with Airbnb.

His is a very intriguing story of how he came into Airbnb, at age 52, as “an award-winning hospitality veteran with a disruptive entrepreneurial streak” and ended up as “an intern surrounded by smart, passionate employees half his age, with twice the digital smarts.”

He was both humbled and inspired by the experience.

From it, he coined two new terms for himself at Airbnb: “modern elder” and “mentern” (part mentor, part intern).

The Airbnb experience appears to have inspired Chip in yet another interesting direction, further igniting his entrepreneurial fires, but this time applying them in more of a not-for-profit, social activist vein.

Conley was recently selected as one of the top 12 “2019 Influencers In Aging” by NextAvenue.org, a subsidiary of the Public Broadcasting System. He is amongst an elite group of “advocates, researchers, thought leaders, innovators, writers, and experts that continue to push beyond traditional boundaries and change our understanding of what it means to grow older.”

Mr. Conley popped up on my radar screen again this week via another interview, this time published in Forbes and conducted by Next Avenue Managing Editor Richard Eisenberg (who I had the good fortune to meet and spend some time with last month at a Retirement Coaches conference in Detroit.)

I encourage you to link to the interview here.

Middlescence – a new cultural portal

In just the last year, Conley has released a new book “Wisdom at Work: The Making of a Modern Elder” and founded a “boutique resort for midlife leaning and reflection” in Mexico called the Modern Elder Academy.

Tagged as the “ first midlife wisdom school”, it has already been attended by 500 students from 17 countries.

Conley’s efforts are inspiring to me, on several levels.

From it, a new and better “cultural portal” classification has emerged – middlescence.

On 7/2/18, I published an article Time For a New Cultural Portal that spoke to how we have, with the help of creative social scientists and enterprising capitalists, expanded from two cultural portals 150 years ago (childhood – adulthood) to seven today (newborn, infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adult, middle age, and old age).

that spoke to how we have, with the help of creative social scientists and enterprising capitalists, expanded from two cultural portals 150 years ago (childhood – adulthood) to seven today (newborn, infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adult, middle age, and old age).

Now, with Conley’s help, we have a better term for that clumsy portal called middle-age and its offspring, the “mid-life crisis” with its sexist, trophy-wife, bling, sports car symptoms.

I think – I hope – Conley and The Modern Elder Academy and the response to it is a sign that we are starting to acknowledge that this phase of life – i.e. elderhood – is beginning a comeback where ageism diminishes and elders are once again held in respect and their wisdom leveraged back into our culture.

Middlescence makes sense in its more definitive description of this (now) extended period of our lives – what I have been calling and will continue to call, the third age.

As the article points out, it generally happens in the fifties and is a time we move from:

Chip Conley is singing my tune.

I hope he is singing yours. I wish I had thought all this up. But I’m OK just being a courier.

My wife of 49 years is, and always has been, a trophy in so many ways; I look terrible with bling and an open shirt collar; a convertible in Colorado just makes an ego trip way too obvious.

“Middlescence” is just what the doctor ordered for my quest.

Are you a “comeback elder”?

How are you preparing for elderhood?

How will you stay relevant?

How will you survive your new longevity? Drifting? Or with purpose?

Important questions for us all as we break through as “modern elders”.

Alzheimer’s Disease and What We Eat

It’s two weeks since attending the funeral service for a dear friend whose battle with Alzheimer’s ended as her body gave in to the complications from the disease.

Our friend Judy’s Alzheimer’s experience was the first with this disease for my wife and me. We shouldn’t be surprised by that since statistically the disease only affects about 1.8% of the American population.

I know it would seem to be so much more prevalent than it is because of the attention it gets. The attention is deserved because it truly is a devastating and costly experience for those close to the victim and to our society.

We can confirm that the impact hugely outweighs its relatively low level of occurrence.

For Judy, her transition from a quiet, warm, giving, serving mom, wife, sister, aunt, grandmother, and friend into a world none of us can comprehend was shockingly quick. Her signs manifested quickly and progressed rapidly.

At least it seemed so for us, but probably not for her husband and two sons who we suspect saw the signs much earlier and protected her, and us, by not revealing those until an official diagnosis was made and the signs too obvious to conceal.

It seemed like almost overnight that our relationship moved from energy-filled golfing trips, card-playing evenings, countless dinners together, years of Bible-study to one where she was a mere incoherent, bewildered body in the room, unable to connect and communicate.

We observed the truth that the disease is much harder on the caregiver than on the victim. Her husband was extraordinary in his love and caring for her to the point where a memory care facility was necessary. The devastating toll on him physically and emotionally was and is palpable. We reached a point in the progression where we realized our focus needed to be on watching and trying to help him get through it.

That continues as a focus for us. They were exceptionally close – he needs and deserves a strong support group going forward to help cope with this void.

No cure in sight.

We know enough about the disease to realize that it is very insidious in nature with the symptoms developing gradually years before the disease noticeably manifests itself. So as we try to attack the disease, our reductionist system of medicine looks more to a cure and less to a cause. My sense is that once the symptoms are apparent, there is nothing at this point in our medical knowledge that can fix it.

It begs the question then why do we not talk and spend more on prevention than on chasing what appears to be an incredibly elusive and perhaps unfixable condition once contracted.

With that thought in mind, an article recently published by the Blue Zones organization entitled “The 2 Foods That Combat Alzheimer’s Disease (& Other Lifestyle Factors to Reduce Your Risk of Cognitive Decline)” caught my eye.

I encourage you to read the article. It’s an interview by “The Blue Zones” author Dan Buettner with a husband and wife team, Drs Dean and Ayesha Sherzai, who are “combating the disease with a comprehensive approach that includes prevention and treatment.” Their book “The Alzheimer’s Solution” espouses Alzheimer’s prevention through a healthy lifestyle.

They state:

“We believe 90% of Alzheimer’s can be prevented through a healthy lifestyle. Despite the resistance towards lifestyle intervention as a tool for dementia prevention, the most recent consensus statement from Alzheimer’s Association is that 60% of Alzheimer’s can be prevented through a comprehensive lifestyle. This number is based on a recent study by Rush University and was highlighted in the media. But we think that they are still understating the influence lifestyle has on Alzheimer’s risk, because their idea of intensive/comprehensive intervention is a watered-down version of what we consider healthy. If people truly live a healthy lifestyle, 90% should be able to avoid Alzheimer’s within their normal lifespan.”

They coined an acronym to help us remember the components of this lifestyle: NEURO

N – Nutrition

E – Exercise

U – Unwind

R – Restorative sleep

O – Optimizing cognitive and social activity

It’s appropriate that N-nutrition is the first letter of the acronym because they come down on nutrition as the most significant Alzheimer’s risk reducer.

That makes sense because that’s consistent with what I noted in my September 30, 2019 article that “our diet is both the number-one cause of death and the number-one cause of disability in the United States.”

This Blue Zones article covers a lot of ground and concludes with the selection of two foods that are best for brain health.

Pretty simple: beans and greens.

How tough can it be to adopt these two natural foods into our nutrition plan?

Well, tougher than we demonstrate. These are not popular components of the fare you will find in fast food places or restaurants in general.

Since we now spend more money eating out than we do to purchase food to eat at home, our current lifestyles are not the venue where we are likely to feed our brains optimally.

I don’t expect that “beans and greens” will ever supplant the pervasive “burger and fries”, “steak and potatoes”, “milk and cookies”, “beer and brat”, “bacon and eggs” American nutrition mindset. But then, life is really nothing more than a series of choices and this is one in which current research is bringing us encouraging news to combat one of the worst debilitations a human can experience.

I dedicate this article to Judy, thanking her for the example of love, sweetness, calmness, and service that exemplified her life. And to her husband whose endurance, dedication, and sacrifice during this very difficult time has been far beyond the pale.

Extend Your Healthy Longevity – Twelve Things That May Be Accelerating Your Aging – Part Three of a Three-part Series.

It’s been a challenge selecting four more topics to wrap up this three-part series on age accelerators to avoid. Not because there is a scarcity of accelerators but rather having so many possible topics to bring forth.

So here’s my final selection of age accelerators to avoid – I hope you find these last four helpful.

1. Holding on to disempowering cultural beliefs. Dr. Mario Martinez, in his books “The Mindbody Code” and “The Mindbody Self”, introduces us to the new language of biocognition – how our culture affects our biology. This language provides a basis for many insights into health or the lack of it. Our cultural beliefs are extremely potent when it comes to our health. They can promote wellness and lead us to joy and happiness or they can cause us to cling to patterns of behavior that are known to be harmful and life-shortening.

Dr. Martinez points out:

“Based on the latest scientific studies of healthy brains, healthy longevity, and a strong sense of self worth, biocognition debunks some very persistent myths: that we are victims of our genetics; that aging is an inevitable process of deterioration; and that the life sciences can simply choose to ignore the influence of culture on human health and well-being”.

Through his extensive global study of centenarians, Dr. Martinez uncovers the empowering and disempowering effect of cultural beliefs and argues that ” – healthy longevity is learned rather than inherited and that the causes of health are inherited rather than learned.” For instance, he uses the term cultural portal to argue that growing older is the passage of time, whereas aging is what we do with time based on our cultural beliefs.

Dr. Martinez uses this example (bolding is mine):

“Middle age is one of the cultural portals. When it begins, your culture will tell you how to behave and dress and what to expect – all without any biological evidence to support that stage of your life. But if you’re not aware that you are in a cultural fishbowl, you will age according to what your culture tells you rather than your biology. Fortunately, there are ways to come out of the portals, as healthy centenarians and other outliers are able to do.”

Does this paragraph make you stop and think? What cultural beliefs might we be carrying forward into the third age that are sub-consciously disempowering us and keeping us from realizing the tremendous potential that remains for us in this period? A few come to my mind:

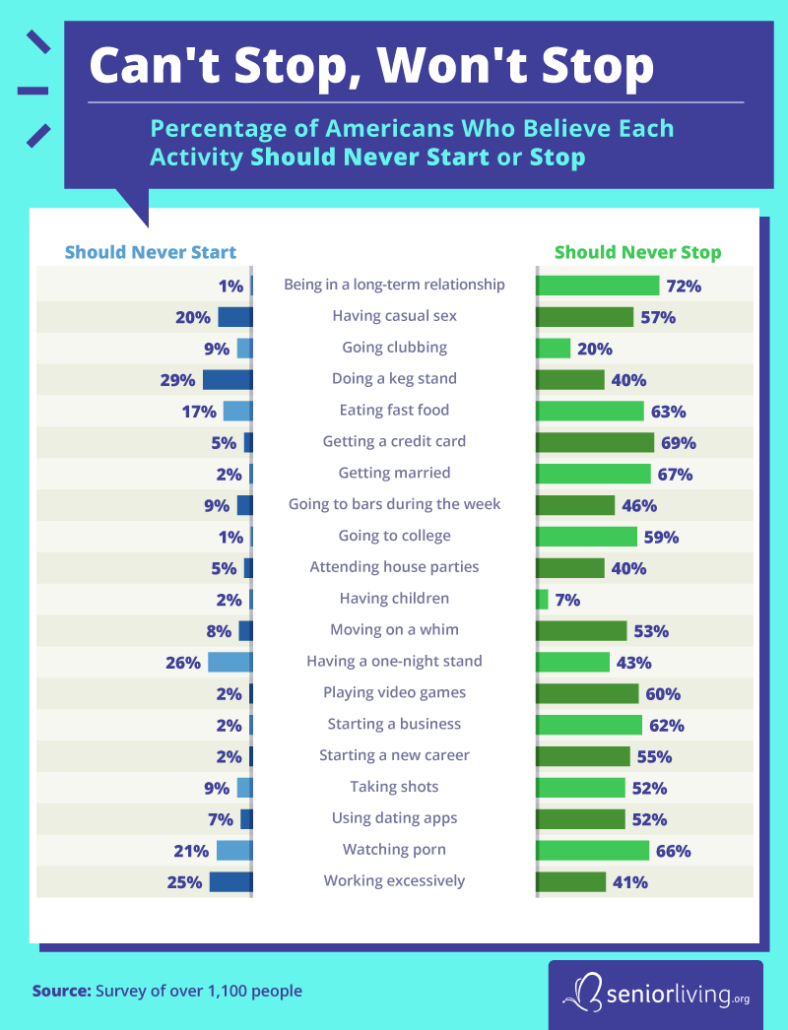

2. Act your age. Here an interesting infographic from SeniorLiving.org from a survey of more than 1,100 Americans about the upper limit age for many behaviors. It pulls together quite a list of cultural activites and how we view adherence to them as we age.

I’m all in on not acting your age.

Spend 3 minutes to view this video by Dr. Roger Landry, former Air Force flight surgeon and respected author of “Live Long, Die Short”. He introduces a new concept called the “dignity of risk.” It says all that needs to be said about not acting our age.

3. Stop being courageous. The dying have a message. Australian hospice nurse, Bronnie Ware, for many years spent time with patients who were in the last few weeks of their lives and who had gone home to die. In her article “Regrets of the Dying, she shares the five most common regrets that they expressed in their final days:

Regret #1 was by far the most common.

For many, being courageous and heeding the call to break out and be true to oneself while progressing into the second half/third stage of life intensifies and, at the same time, becomes increasingly difficult.

4. Losing a sense of purpose and meaning. Dr. Robert Butler was a world-renowned gerontologist, psychiatrist, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning activist and aging pioneer who coined the terms “ageism” and “longevity revolution. The Blue Zones website reports that Dr. Butler and his collaborators led an NIH-funded study that looked at the correlation between having a sense of purpose and longevity. His 11-year study followed healthy people between the ages of 65 and 92 and showed that those who expressed having clear goals or purpose lived longer and lived better than those who did not. This is because individuals who understand what brings them joy and happiness tend to have what we like to call the Right Outlook. They are engulfed in activities and communities that allow them to immerse themselves in a rewarding and gratifying environment.

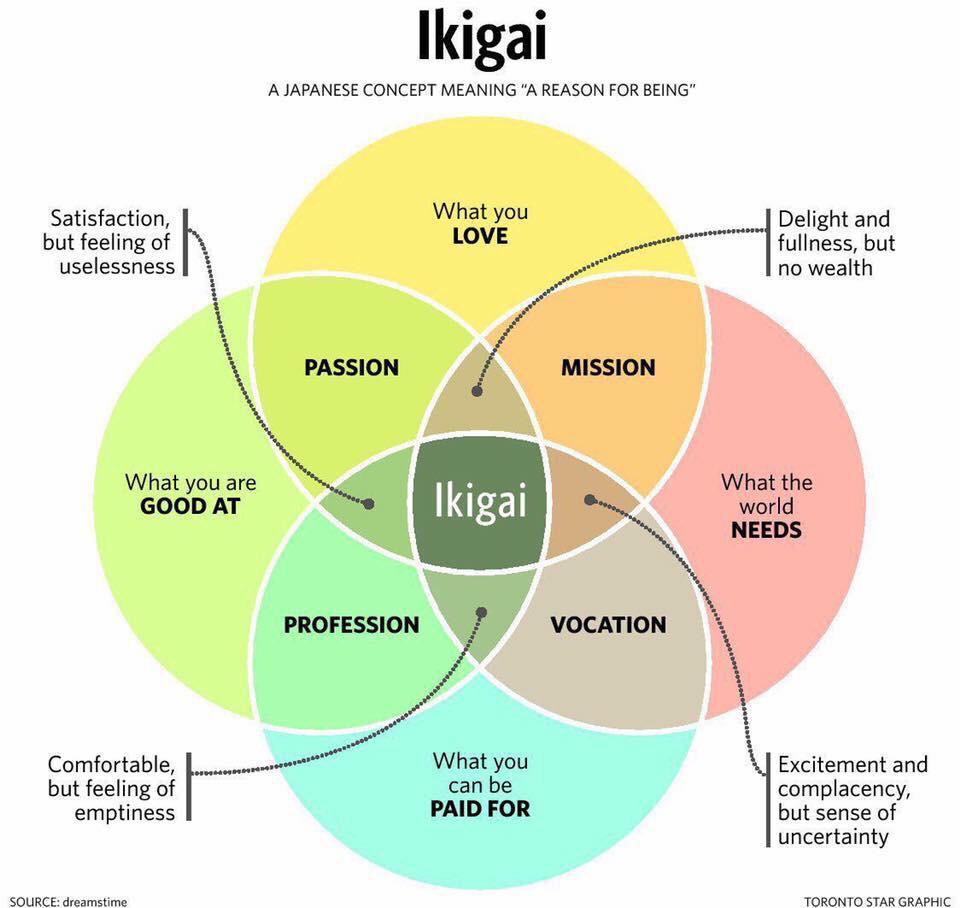

In Okinawa, where we find one of the highest percentages of people living to 100 or beyond, they have a term for sense of purpose – ikigai. It stands for “why I wake up in the morning”.

Extend Your Healthy Longevity – Twelve Things That May Be Accelerating Your Aging – Part Two of a Three-part Series.

Thanks for your feedback on the first article in this three-part series. A special thanks to loyal reader, Roger Knisely, for suggesting that I “flip the script”. So I’ve changed the headline and will try to put a more positive spin on the next eight items over the next two weeks.

Here are four more age accelerators for your consideration:

Let me have better authorities than me do the talking about this since you may be tired of my tirades.

Food journalist and author, Bee Wilson, published this article in The Guardian that says it better than I can. It’s a long article so just in case it’s more than you want to read, here are a few extracts that get to the core message (bolding is mine).

“For most people across the world, life is getting better but diets are getting worse. This is the bittersweet dilemma of eating in our times. Unhealthy food, eaten in a hurry, seems to be the price we pay for living in liberated modern societies. It makes no sense to presume that there has been a sudden collapse in willpower across all ages and ethnic groups since the 1960s.”

“What has changed most since the 60s is not our collective willpower but the marketing and availability of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods. Some of these changes are happening so rapidly it’s almost impossible to keep track. Sales of fast food grew by 30% worldwide from 2011 to 2016 and sales of packaged food grew by 25%. Somewhere in the world, a new branch of Domino’s Pizza opened every seven hours in 2016. You can measure this life improvement in many ways, whether by the growth of literacy and smartphone ownership, or the rising number of countries where gay couples have the right to marry. Yet our free and comfortable lifestyles are undermined by the fact that our food is killing us, not through lack of it but through its abundance – a hollow kind of abundance”

“Most deaths in the United States are preventable and related to nutrition. According to the most rigorous analysis of risk factors ever published, the Global Burden of Disease study, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, our diet is both the number-one cause of death and the number-one cause of disability in the United States, having bumped smoking tobacco down to number two. Smoking now kills about a half-million Americans every year, whereas our diet kills thousands more.”

As in so many health-inducing solutions, the resolution is simple, but not easy. Renowned food author Michael Pollan’s now-famous seven words illuminate the path: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” You’ll find those pithy words, along with 80+ other life-saving nutrition-focused suggestions in his wonderfully simple and readable book “Food Rules”.

Our taste buds have been taken and held captive for decades by carefully engineered and designed combinations of sugar, salt and fat, designed by our global food industry to promote cravings rather than satiation. Our bodies are called on every day to fight a battle against this invasion. Maintaining the Standard American Diet is to lose this battle insidiously before our time should be up.

A largely plant-based diet can be the age decelerator.

2. Limited or no aerobic exercise and no strength training. “Aerobic exercise will give us life; strength training will make it worth living.” So says the late Dr. Henry Lodge, co-author of the life-altering best-seller “Younger Next Year”.

Last week, I suggested that we become better at understanding our biology. Fundamental in that understanding is that our cells need and crave oxygen. The only way to increase the amount they get naturally is by getting our heart rate up.

The only way to increase the amount they get naturally is by getting our heart rate up.

Voila!! Exercise.

Dr. Lodge does a masterful job of bringing that complex process down to an understandable level. It was his explanation that motivated me to move a modest, sporadic exercise schedule to a six-day-a-week aerobic exercise routine of 45 minutes per day. If I miss it, I envision my cells shaking their fists. That motivates me to get on a boring upright bike or treadmill. Thank goodness for my Kindle!

Most people north of fifty shun resistance training/weight lifting. That’s for the younger set, they say – the tattoo and tanktop and lululemon hard-body crowd at 24-Hour Fitness. Dr. Lodge takes the opposite position. Strength training in your 30s or 40s is optional. At 50 and beyond it is imperative.

Why! There’s this condition that we all begin to contract in our late thirties called loss of muscle mass (commonly referred to as sarcopenia) that really accelerates when we reach fifty. There is no drug to treat it – you can only counter it by doing resistance training.

Be sure to consult with your physician before starting and I suggest starting with a professional trainer who has worked extensively with mid-life and older clientele.

3. Being a hermit. A recent article in Medium.com contained an attention-getting sub-title: “Lonely people are 50% more likely to die prematurely than those with healthy social connections.”

In 2016, the AARP Foundation announced that the health risks of prolonged isolation are equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Our wi-fi connections are getting better but our personal connections are going south, especially when we enter into the post-career phase of our lives. The promotion of full-time, leisure-based retirement steers starry-eyed retirees into “golden years” that often evolve into “lonely years.” We retire, we move away from our roots, friends move away, we become generally less-socially active. The expectation that our “work playmates” will “stay in touch” doesn’t happen. Health issues may cause us to restrict our ability to travel to maintain our social engagement.

The AARP study revealed:

Building and maintaining an active, positive, sustaining, and available network of people requires a pro-active approach. Here’s a link to a brochure that has a self-assessment checklist to gauge your risk of isolation and its effects.

4. Be done with learning. Some time ago, I did some research for a Toastmaster speech on the “state of reading” and was surprised by what I found.

I have a college-degreed, septuagenarian friend who proudly boasts of having never read a book since graduating from college. For him, and the many like him, I offer up this wisdom for consideration:

“Anyone who stops learning is old, whether twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning today is young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young. ” Henry Ford

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s partner of 40 years, says there’s one quality of Buffett’s that he holds in especially high esteem: his ability to be a lifelong “learning machine”. At 89, Buffett still spends 5 hours a day reading – often up to 500 pages a day.

Today, we are the benefactors of new knowledge about your brains. Dr. Roger Landrey, preventive medicine physician, former Airforce flight surgeon and author of “Live Long, Die Short: A Guide to Authentic Health and Successful Aging points out that

” Atrophy of the brain used to be viewed as a side effect of aging. Now, we know this may simply be a lack of use.”

If we don’t use it, we lose it.

Dr. Landry goes on to say:

” When we use the skills and knowledge we have, the many connections in the brain remain in the best shape they can be. Don’t use them, and they become more difficult to use through a process known as synaptic pruning, in which the brain atrophies in areas where these functions are rarely used. Neuroplasticity and effective neurogenesis can only occur when the brain is stimulated by environment or behavior.”

It’s encouraging to see the trend line in adult learning turning up. Boomers are awakening to the benefit of continued learning. The evidence of this is showing in the increased enrollments in adult learning classes at universities and community colleges and the many online learning communities such as Senior Planet, Osher Lifelong Learning Institutes (OLLI), Coursera, Udemy, and others.

The choice to stop learning is a choice that says “I’m done.” As Strategic Coach founder Dan Sullivan says: “It’s a signal to the universe that you are preparing to send your parts back.”

Four more aging accelerators to come next week. Thanks for your feedback. Please let me know your thoughts on these four – or on the series so far – by scrolling down and leaving a comment.

Also, if you haven’t, subscribe to our weekly newsletter at www.makeagingwork.com and receive a copy of my free ebook entitled “Achieve Your Full-Life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Extend Your Healthy Longevity – Twelve Things That May Be Accelerating Your Aging – A Three-part Series.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

“Life is a fatal disease. Once contracted, there is no known cure.”

This is a quote from Dr. Walter Bortz, one of my favorite authorities on maintaining good health in our third age. Dr. Bortz is an 89-year old former Stanford University geriatric physician and author of seven books, my favorites being “Dare to Be 100” and “The Roadmap to 100”.

While his quote has a bit of a fatalistic tone, his written and spoken advice takes a much more optimistic tone about delaying the “fatal disease” part of life.

Dr. Bortz convinced me, when I read “Dare to Be 100” the first of three times in 2013, that I needed to ratchet up my own longevity expectations. Prior to reading his reasoned and experienced position on successful aging, I hadn’t given it a lot of thought and was pretty fatalistic in my longevity expectations.

Kind of the “what will be, will be” – with a sprinkling of naivete about the non-role of genetics in my longevity.

So with a fresh understanding from Dr. Bortz that there is no biological reason that the human body shouldn’t last well past 100 years, I began confessing to the goal of living to 100. I’ve since revised that to 112 ½ years because, at 75, I decided I need another third of my life to catch up for what didn’t get done in the first two-thirds.

Yes, my friends and family still think I’m nuts but no longer roll their eyes – probably out of boredom, deference, and pity. Candidly, I am probably nuts to think it will happen. With mild hypertension, hypothyroidism, atrial flutter, and statin-controlled cholesterol, I’m probably not the best horse to bet on in this race.

No, I’m not going to be a part of the statistic. Too much to do in my quest to instill sageism and fight ageism.

Yeah, we aren’t going to get out of this thing alive. But we don’t need to hasten the demise. Culturally, we’re really good at building age accelerators into our lifestyles, often innocently and due to lack of knowledge, more often just out of laziness, lack of discipline, capitulation to convenience and a refusal to acknowledge the insidious nature of habits.

How might you be accelerating your aging? Here are the first four of a dozen accelerators I’ll toss out over the next three weeks for you to consider and check yourself against :

William James wrote: “Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help make it so.” Tony Robbins reminds us that it’s impossible to be grateful and depressed at the same time. Think lofty thoughts and be grateful for each day.

Brianna West, author and blogger at Thought Catalog offers up some insight in both areas:

“There’s no such thing as real comfort, there’s only the idea of what’s safe. This one is a big one to swallow, but there’s really no such thing as “comfort,” which is why comfortable things don’t last, and why the best-adjusted people are most “comfortable” in “discomfort.” Comfortable is just an idea. You choose what you want to base yours on.”

“There’s no such thing as true security. We seek comfort believing that it makes us safe, but we live in a world in which there is no such thing as true security. Our bodies were made to evolve, our physical items are temporary and can be lost and broken, etc. To combat this, we seek comfort, rather than accepting the transitory nature of life.”

Lori Bitter of The Business of Aging.com and author of “The Grandparent Economy” found, in extensive research she recently conducted, that “baby boomers know what they should be doing – they just don’t do it. It generally takes a crisis to provide the stimulus to make the changes they know they should be making.” We choose to ignore what we know that can slow age acceleration.

In addition to either of the two books by Dr. Bortz mentioned at the top, I suggest a trip through a great transformational book on this topic entitled “Younger Next Year”, a must-read for anyone wanting to push that endpoint further out.

These four age accelerators get us started. Eight more to follow over the next two articles. Tune in next week. Please leave your comments below about this quartet of accelerators.

Health alert: Get to Know Your PCP!

How well do you know your primary care physician (PCP)? Have you been with him/her for a long or a short time? How old do you think s/he is? How long in his/her practice?

These aren’t questions we’re inclined to spend time thinking about.

Maybe we, as third agers, should be more attentive to this relationship. Because there is an intensifying shift in the physician space that has been going on for a number of years that can affect our ability to get the care we may need as we get older.

If you’ve followed me for a while, you know I’m not a big fan of the healthcare system here in the U.S. (Note: my apologies to my non-U.S. followers. I’m going to be talking about what I understand to be largely a U.S.-centric issue).

If you are like most, your first point-of-contact when a health issue comes up is your primary care doc (PCP) who is most likely a primary care or family practice physician. They are generalists who treat adults (and children, in a family practice) specializing in the prevention, diagnosis, and management of disease and chronic conditions.

Like many things in life, we take them for granted, assuming they’ll be there when needed.

But that may be changing – and within our lifetime.

I’ve had a bit of a front-row seat to the machinations taking place in the healthcare space over the last 17 years as an executive healthcare recruiter. Over the last seven years, that involved recruiting specifically for small to large medical practices, some of which were internal medicine and family practice organizations.

When I moved my recruiting business to that healthcare segment, a major shift in the makeup of physician practices was well underway. Many independent medical practices, especially internal medicine and family practices, were struggling to survive because of the tremendous burden of regulations, insurance, and billing issues.

In particular, one of the major culprits in this shift was the advent of the electronic medical record system foisted on practices by the government. It has turned out to be one of the great disasters within our healthcare system history and is driving many physicians out of their practices.

Many internal medicine and family practices consolidated to try to achieve economies of scale. Or they scurried under the wings of hospitals to relieve the burden of running the office side of the business which stole from their ability to “be a doctor” and practice medicine.

Follow the money

For years, physicians-to-be have been selecting the more “prestigious” and higher-income specialties such as orthopedic, anesthesiology, dermatology and others and avoiding the family practice/internal medicine path. Much of this is being driven by the fact that primary care specialties are amongst the lowest-paying specialties.

It’s now becoming a national problem – one that could affect us in the coming years.

According to a 2019 study conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) the United States will see a shortage of up to nearly 122,000 physicians over the next decade, including up to 55,000 primary care physicians.

Kaiser Health News recently reported that in 2019 the number of internal medicine positions offered was the highest on record – over 8,000. Only 41% were filled by graduating seniors pursuing their medical degrees from U.S. medical schools.

Given this backdrop, we need to recognize that it’s going to be increasingly difficult to find a primary care physician that will accept us as a patient. Fewer are coming into the system and older docs are retiring out at an earlier age.

Burnout is a growing issue

Forty percent of males physicians and fifty percent of female physicians are burned out because of high patient loads, the hassles of running a practice, electronic medical record requirements, and government regulations – all while reimbursement rates under Medicare are declining.

This condition isn’t likely to get better, certainly not in our lifetimes.

So what is one to do? Here are three proactive things you may want to consider:

One possible solution to consider: a relationship with a concierge practice where, for an annual fee, you are guaranteed unlimited access to a doctor who really does want to practice medicine. The model is built on reducing patient enrollment from several thousand down to 5-600 and offering more personalized service.

One of the primary care docs I was with for a short while admitted to having 4,800 patient charts. The average appears to be around 2,500 for primary care physicians. Concierge-style practices can be relatively expensive, and there can be some insurance coverage issues, but I’m told it’s an environment where you can truly partner with your physician.

So, to recap.

We need that PCP but we needn’t relinquish our health to them. Be sure you are positioned with one that is going to be around for a while and engage him/her at a deeper level letting them know you are becoming more knowledgeable ( with her/his help), that you are taking charge, and really want his/her help on this journey.

I believe you will get a very positive response from the doctor. One, because they get that from very few; two, because you are asking them to do what they really want to do – be a doctor.

You will quickly discover, from the response, if this is someone you want to continue with –or whether it’s time to initiate a search for someone else.

This shortage is not likely to get the attention it needs from the government or, surprisingly, from the medical community itself. It’s lost, along with all the other critical issues that are going nowhere in Disneyland on the Potomac.

It’s on us. Don’t wait until it’s too late.

Let me know of your experience in this area – positive or negative. We welcome your feedback on this topic – scroll down and leave a comment below.

Celebrating #100!!

Well, dear readers. This is blog #100.

My thanks to those of you who have endured my iconoclasm, sarcasm, rants, wanderings, mild plagiarism, and occasional drivel for the last two years and still open the weekly email.

I never imagined getting this far down the blogging road. According to one source I came across, most people who start blogs quit within 3 months.

My ego would naturally take that and say that I’m 8x better than most, but we all know that’s garbage. I’m just afraid to quit because once in a while some of you give me a stroke that hints that someday I may grow into being a real writer.

Given that there are over 600 million blogs in the world today and that 77.8 million blogs are published each month on WordPress and that 2 billion blog posts are being published each year worldwide – well, my sanity is up for question.

are being published each year worldwide – well, my sanity is up for question.

But some of you knew that even before I put my keyboard to a blog.

In recognition of #100, and to relieve you having to sort through and decipher another mini-epistle, I’m doing something a bit different this week.

I collect quotes. Hundreds of them. It helps me maintain my reputation as someone who can “cliché you to death.”

In our recent move, I uncovered a couple of forgotten boxes crammed with 3×5 cards with notes and quotes from books and articles I’ve read as far back as 20 years.

Hundreds of cards.

I’ve begun an 80% gleaning, narrowing my arsenal of clicheic hammers.

From that gleaning, I decided to share a few humorous and pithy quotes that I felt you might enjoy. Most of these came from a single Forbes article.

Thanks for being a reader. I’m looking forward to the next 100!

Thoughts on work

Thoughts on ambition

Thoughts on health

Miscellaneous

See you next week

Does Your Favorite Presidential Candidate Have a Food Platform?

Hold on – I’m not going all political on you. I’m in the same place you are – dumbfounded by how far off the tracks we’ve gone in government leadership and common sense.

That’s stuff for another article – somebody else’s article because I’m not writing it.

But a New York Times piece entitled “Our Food Is Killing Too Many of Us” recently hit my newsfeed. It reminds us that we “Americans are sick – much sicker than many realize.” It refers to the CDC report that more than 100 million U.S. adults are now living with diabetes or prediabetes. Breaking down the CDC report, it appears that about 10% have diabetes, 90% have prediabetes which, if not treated, can lead to Type 2 diabetes within five years.

If you’ve been enduring my articles for a while, you know that I unabashedly boarded this “food is killing us” bandwagon long ago and continue as a lonely voice in a wilderness of fellow sapiens whose taste buds and habits have been taken and held captive as we slowly eat ourselves to death.

Along with the planet!

OK – I’m not going all environmentalist on you either. But, at some point, we’ve got to get real about all this.

Think about it – have you heard one garlic-laced utterance from any of the several thousand presidential candidates that included the word “food”?

How many of them know or care that it takes 600 liters of fresh water to produce one liter of any sugar-sweetened soda delivered in a plastic bottle. Or that, according to Soil and Water Specialists at the University of California Agricultural Extension, the water required to produce one pound of beef is 5,214 gallons.

Please assure me you won’t be holding your breath waiting for any of the above to cross the lips of any candidate, right or left.

What we can count on is the continuing political dance that steps over the problem to focus on how to ensure that the financial injury for bad health habits isn’t egregious. Nary a poke at the source of the problem – poor eating habits, lack of exercise, a food industry that thrives on government inaction and a populace ignorant to what they are doing to themselves.

Oh, and we had best throw in a healthcare system that struggles to spell “food” and would go apoplectic if asked to define “nutrition.”

The Times article acknowledges that government plays a crucial role:

“The significant impacts of the food system on well-being, health care spending, the economy, and the environment — together with mounting public and industry awareness of these issues — have created an opportunity for government leaders to champion real solutions.

Yet with rare exceptions, the current presidential candidates are not being asked about these critical national issues. Every candidate should have a food platform, and every debate should explore these positions. A new emphasis on the problems and promise of nutrition to improve health and lower health care costs is long overdue for the presidential primary debates and should be prominent in the 2020 general election and the next administration.”

I suppose we could hope it will happen –the political “food platform” thing. Nothing wrong with being hopeful but I’m inclined to put hope and wish in the inaction category. Does it make sense to wait for a political “food platform” to emerge from the tangle of trade wars, border conflicts, space defense, buying frozen countries, and free everything for everybody?

It starts with us. And our nutritional and environmental awareness. We don’t do well with the first and ignore the impact of the latter.

Meat equals money and our appetite for meat is the most direct cause of the Amazon’s peril along with other parts of the world with the U.S. near the top of the list.

Carefully engineered combinations of sugar, salt and fat are a direct cause of our sickness. We are victims of our own naivete, reprogrammed taste buds, and craving for convenience. Given all that, we individually are still the only solution.

Consider this suggestion from nutrition activist and physician Dr. David Katz ( the bolding is mine):

“Eat less meat this week. If you eat it daily, skip a day. If you only eat it weekly, skip the week. If you, personally, had to set some majestic, 200-year-old tree on fire as a prelude to your next bacon-cheeseburger, would you do it? Those of you who say yes are beyond redemption. To everyone else: eat less meat, please. This is the price it is exacting- unattenuated simply because someone else strikes the match.

Less ultra-processed food, less meat, and more whole plant foods are the very formula most indelibly linked to less chronic disease, less premature death, less obesity, more years in life, more life in years. But in this context, that is simply fortuitous.

There are no healthy people on a ravaged planet. There are no healthy people on a planet that can no longer sustain them. We are at risk of eating ourselves into extinction.”

Thanks for allowing me back up on my soapbox. Feel free to knock me off with a comment below if you feel differently. My-fruit-and-vegetable-and-wholegrain-fed skin is getting thicker.

////////

P.S. How fortuitous. Just as I finished this article, a newspaper headline in our daily rag called the Denver Post said the following: “Trump administration limits scientific input” with a tag “USDA Dietary Guidelines”. We now know that one presidential candidate, and his administration, have a “food platform”. It indirectly supports the consumption of meat, highly processed and high sodium foods by eliminating questions about those issues from the 80 questions that the committee overseeing nutritional guidelines have been asked to explore. If you read the article, I hope you come away a bit incensed.

Have You Put An Expiration Date on Learning?

“Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one’s self-esteem. That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily, and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.”

So says Thomas Szasz, Hungarian-American academic, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst.

Mr. Szasz’s statement sort of pissed me off. Cannot learn at all? C’mon, I’m learning something new every day at 77.

I’ll bet (I hope) you are too.

I’ll confess, it’s a tad harder. Well, maybe more than a tad. My brain’s CPU seems to be stuck at Windows XP and the hard disk could use a partial download to the cloud to free up some space.

But not at all, Mr.Szasz?

They just finished a full-week of drama camp and both had significant roles in the play that wrapped up the week.

My wife and I weren’t able to attend the play. During their visit this week, my wife asked them to do their parts for us.

Our culture hasn’t gotten to them with the “self-importance” thing yet. With these two, you always get a bit more than you bargained for – in energy, enthusiasm, craziness. With this request, they didn’t disappoint.

They did THE WHOLE PLAY for us!!

That’s right – their parts and everybody else’s part. Dances included. And with some of their own improvisation sprinkled in. A full week after the performance.

That same day, I couldn’t, for the life of me, remember a quote I had read earlier that I wanted to capture. Nor could I even remember the book I read it in (I have four books going right now).

So maybe Thomas has a point. But I’m not willing to concede on the “at all” part. I’ll concede on the speed thing, both in learning and retrieving, but not on my ability to continue to learn, and learn deeply.

In fact, since I’ve lost my sense of self-importance (please, don’t cross-check that with my wife), I’m learning at a faster clip and in more volume than I was 20 years ago when I was in the middle of building self-importance in the corporate world.

With titles, position and the opinion of others now in the back seat, I’m highly motivated to continue to learn what I want to learn.

My reading is more focused on my life quest and has shifted to more non-comfort-zone reading. Best selling author, Stephen J. Dubner , author of “Freakonomics” and “Superfreakonomics”, was right when he said: “most ‘important’ books aren’t much fun to read. Most fun books aren’t very important.”

I’ve read several un-fun books this past year and have been stretched in the process.

I’m also trying to write something daily that pushes me outside my comfort zone – like this article.

My Toastmaster Club gives me an opportunity weekly to stretch, test, and refine my speaking skills, both prepared and impromptu.

I wish all this was coming up roses. I will admit to continued frustration with the failure to retain the information I read and with the fits and starts of my progress in both writing and speaking.

After reading over 500 books over the last decade, I confess that I have retained very little of what each book said. I can look at the cover of a book on my “favorites” shelf and honestly not be able to tell you much of what I learned from it that was significant.

When a good friend recommended a book called “Peak. Secrets From the New Science of Expertise” by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool, I did my usual thing – I bought the cheapest used paperback copy on Amazon.

As is often the case, it was a timely injection into my reading stream. I read it in five days of early morning reading time. It is replete with highlights, margin notes, paper-clipped pages and colored tabs protruding from the side that mark the mega-important pages.

It’s the quirky way that I attack books. It’s also why I NEVER lend them out or why I can’t recycle them to a used-book grave because they are such a marked-up mess.

But I’ve been doing that with books forever, and I still can’t remember much of their content.

Ericsson’s book may be the catalyst that will change all of that for me – and perhaps for you if you are experiencing similar frustration with retaining and applying what you’ve learned. Ericsson’s research appears to have the key to unsticking me from a handful of stuck areas in my life – reading retention, writing and speaking with impact, frozen golf handicap, plateaued guitar playing – to name a few in my life.

Ericsson’s extensive research and human experiments on memory retention reinforce the point that, like a computer, our brains have short-term memory (RAM) and long-term memory (hard drive). We’ve known for decades that there is a limit to what our short-term memory will retain. It’s designed to hold small amounts of information for a short time.

That’s why you forget the new neighbor’s name fifteen minutes after you met them unless you do something to move it out of short-term to long-term memory – such as repeating the names over and over again until the transfer takes place.

Our brains have a strict limit on what they can hold in short-term memory. The average limit is seven items, which explains why we have to write ten-digit phone numbers down rather than expect to remember them (it doesn’t get easier as we get older, have you noticed?)

Ericsson’s experiments and research confirmed that, unlike short-term memory, long-term memory doesn’t have an upper limit, but takes much longer to deploy.

He provides examples throughout the book of truly amazing feats of memory to illustrate this quality of our brain. His cornerstone experiment involved working with a bright, young Carnegie Mellon grad student testing his ability to present digits that were read to him at the rate of one per second – too fast to transfer them to his long-term memory. Repeating them back to Ericsson, the student continually hit the wall at number sequences eight or nine digits long.

But, over two years and two hundred training sessions, the student successfully remembered eighty-two digits read to him one per second.

Eighty two!!

He did it by refining a mental process for moving the digits to his long term memory.

Using other examples of exceptional performance throughout the book – blindfolded chess players, record-holding cyclists, typist exceeding 200 words per minute, basketball free-throw shooters – Ericsson concludes that “no matter what field you study, music or sports or chess or something else, the most effective types of practice all follow the same set of general principles.”

It’s not about genetics or innate talent.

Wanna be a “grandmaster?” I know, few of us do because we don’t think we have the “innate talent.” But if we did want grandmaster status, we would have to accept that high achievement is not rooted in intelligence or inborn talent.

It’s rooted in practice, deep deliberate practice.

In Ericsson’s words: “The answer is that the most effective and most powerful types of practice in any field work by harnessing the adaptability of the human body and brain to create, step by step, the ability to do things that were previously not possible” and that “- all truly effective practice techniques work in essentially the same way.”

I had read other similarly-themed books about deliberate practice, the secondary role of talent versus effort, the significance of 10,000 hours to master something (Geoff Colvin’s “Talent Is Overrated”; Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers”, Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code”) and have had the “head knowledge” of what separates the great from the good from the mediocre.

Ericsson’s book caps that little library and is providing a eureka moment that, as I write this, is inspiring me to move what I’ve learned from my head into practical application, starting with forgiving myself for the years of wasted surface-level practice along my vocational path.

My braggadocious posture about reading 75 books a year is now not only embarrassing but also reveals my naivete about meaningful learning. It represented “notches on the gun”. It was get-that-one-on-the-shelf-and-get-on-to-the-next-one, searching for that magic quote, sentence or paragraph that will turn my success ship.

Previously, I would finish every book, even if it wasn’t reaching me. I’m over that. I’ve learned that many books are fluff and a waste – and that not every book has its time and space in my world. If it isn’t reaching me but there is a hint of something valuable, I will now shelve it and maybe come back to it and see if its time has come.

Before, if I finished a book that really reached me, I’d finish and shelve it on my “A” shelf, only occasionally coming back months or years later to reread it. No more of that either. I now stay with the book and try to move as much of the really important content to my long-term memory by rereading the highlights/paper-clipped/colored-tab pages and then (I know this seems nutty!) writing the really, really good stuff on 3x 5 cards to keep in the book.

Those are my cliff notes for further review down the road.

Four levels of practice.

Reflecting on “Peak”, it is clear that we can choose the level of expertise or mastery that we want, independent of innate talent. Colvin, Gladwell, and Coyle also said that in their books.

And we can do it at any age, even as a third-ager.

We have four practice choices as we move forward in life:

No practice

This is the default and where many of us end up. Accepting our fate; maintaining the comfort of the status-quo; conceding to our inherent laziness; not understanding how our brain/body works at its best; being goalless, drifting and led, not leading. Then we hit the death bed and express regrets for never having taken any risks – or worked hard at getting good at something worthwhile.

Practice

This is “naïve practice” which is essentially just doing something repeatedly and “expecting that the repetition alone will improve one’s performance”, according to Ericsson. It’s practice without clear goals, no feedback mechanism, no stretch. This too is comfort-zone territory.

This is me for the last twenty years on the driving range with $7 buckets of balls hitting them with no sense of what needs to be fixed, no one to give me feedback on why most are mishits, deepening the defects in my swing and making it harder for a coach to coach them out of me.

It’s “doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results” defined by Einstein as “insanity”. That shows up often in my guitar playing where I sit and entertain myself by playing stuff I already know well and not pushing myself to add a new tune, technique, new rift, or extending my hand stretch.

It’s doing a sales call using the same script/pitch over and over and wondering why prospects aren’t converting and thinking that “they” will eventually get smart and change if you just stick with it long enough.

Purposeful practice

In contrast, purposeful practice is more purposeful and focused. According to Ericsson and Poole, purposeful practice has the following characteristics:

I love golf. My 22 handicap has not moved in ten years. The last few years, I’ve been tracking several components of my game: fairways hit, greens-in-regulation, chips/pitches, putts. The glaring deficiency in my game is greens-in-regulation – my ball is invariably on the green one or more shots more than it should be to make par. I average a paltry two G-I-R’s per eighteen-hole round. No magic here. My approach shots stink, meaning that’s where my problem lies.

I’m setting the goal for this season of an average of six G-I-Rs and a handicap of 18. I’ve already taken lessons from a pro and know what to do – learn to make a freaking approach shot!

Deliberate practice

Most of us would do well to get from “naïve” practice to purposeful practice. That move alone can produce amazing results.

But there is yet another level of practice, according to Ericsson, that is the “Gold Standard”. It’s called deliberate practice – it’s purposeful practice on steroids.

Here are a couple of examples:

Here’s what I learned from “Peak” about “deliberate practice” and how I will be applying it:

It’s revelatory to track the path followed by some of the world’s greatest achievers and learn that “prodigy”, “innate talent”, “genius” rarely applies. Time and practice mark the path of high achievers.

And that they don’t stop learning as they age.

So Mr.Szasz, with all due respect, I’ll keep learning – because I can. And I must. My string, and that of my compatriots in this “older person” category hasn’t run out. If we’ve stopped learning, we’ve made one of the most unfortunate mistakes we can make if we wish to live a longer, healthier life.

Your thoughts are welcome – please scroll down and leave a comment.