You do know that retirement is invented and not natural, right?

We appear to be the only species that decides to voluntarily push ourselves toward a state of accelerating physical and mental decline and deterioration.

As opposed to the natural world, where it’s involuntary and usually abrupt – as in dead.

The silver maple in my backyard is showing signs of giving it up, ravaged by 10 years of persistent Colorado drought conditions. Some spring soon I expect the leaves won’t appear and it will be over and leave a gargantuan removal task.

I know the mother red fox that frequently sits underneath it will keep hunting, digging, delivering kits, and surviving until she can’t and something – or someone – takes her out.

Non-existent 150 years ago.

Retirement didn’t exist anywhere on the planet 150 years ago.

My maternal grandparents homesteaded on a quarter section of free government land in rural Wyoming around 1905. No water within a half-mile, no wood to build a house, lived in a covered dugout for a year while they dug a well and poured a concrete house.

Homestead house – still standing 100 years later.

No indoor plumbing until 1958, my sophomore year in high school. Reports of two-holers with Montgomery Ward catalogs are not a myth, trust me.

They scratched a subsistence-level existence off this hard-scrabble parcel and worked themselves to death, giving it up in their early sixties after spawning four children, three of which made it past 16.

The idea of retirement didn’t exist in their world. It was work, survival, and family to the end. And family made the final transition loving and comfortable.

They hadn’t heard about Otto von Bismarck’s plan.

Back in 1889, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck invented the idea of retirement, claiming that: “Those who are disabled from work by age and invalidity have a well-grounded claim to care from the state.” It sounds very altruistic; however, the truth is, he was buying back votes in that cohort that he was beginning to lose to the Marxist movement.

Humanitarian? Or political? You decide.

Otto gets the blame or the credit for the concept of human retirement, depending on your mindset.

FDR went to school on ‘ol Otto and gave the concept a big boost in 1935 as he teamed up with big businesses and unions (maybe the only time that has happened). Together they carved out a political solution to the problem of unemployed young men rioting in the streets by establishing an arbitrary retirement age of 65 to move older workers out and younger workers in.

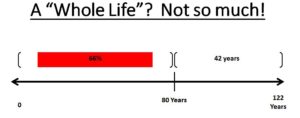

Made some sense since few people lived that long (average lifespan at 62). The prospect of getting “have fun, beach or bingo” money for 2-3 years made sense.

So the origin of this thing that still pervades our psyche so deeply 87 years later is both unnatural and politically inspired.

And an incredible bonanza for creative insurance salespeople who have profited mightily by convincing us that a no-work life filled with leisure is the healthiest option for the later stages of life.

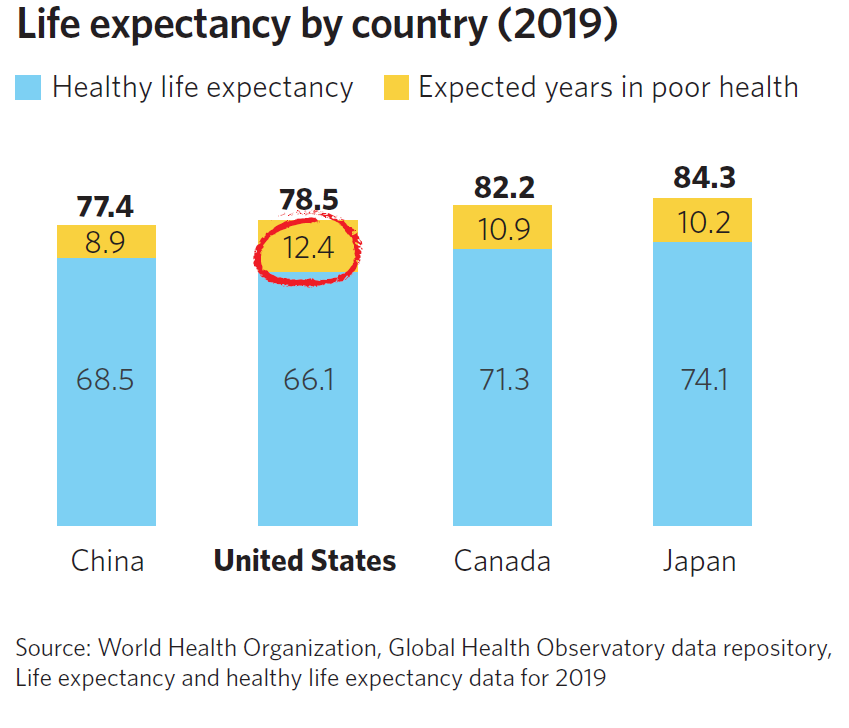

Is the fact that our average life expectancy has been receding over the last 5 years and that we experience, on average, 12 years of ill health in the U.S. before we die evidence that a retirement lifestyle may not be the healthiest?

Agreed – those conditions are more likely a throwback to earlier lifestyle decisions, but it’s hard to argue that a full-stop retirement does anything to slow or reverse them.

What if it didn’t exist?

Pretty hard to imagine, isn’t it. At least here in the U.S. – and in many western cultures.

But, there are cultures where retirement doesn’t exist – at least, not in the off-the-cliff, labor-to-leisure form that has characterized most retirements in the U.S. over the last 50 years. And, surprisingly, these cultures present a counterargument to the western logic that drives our infatuation with a concept claiming that a no-work retirement is a healthy lifestyle option.

You may be familiar with the research done by Dan Buettner of National Geographic that culminated in the book “Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who Lived the Longest.” Buettner and his crew of demographers identified five locations where people lived the longest and healthiest lives anywhere on the planet.

You can go here to see the nine commonalities that led to longer, happier, healthier lives in these communities. You’ll notice that retirement isn’t included. In fact, Buettner reports:

“In Okinawa, there isn’t even a word for retirement. Instead there’s simply ‘ikigai,’ which essentially means ‘the reason for which you wake up in the morning.'”

OK, I’m all in on escaping a grinding, meaningless, purposeless, stress-filled job. It makes little sense to continue that for 30-40 years in pursuit of an idea that offers up false promises and is a trojan horse for a deteriorating healthspan.

What if we started over and acknowledged that putting an arbitrary use-by time stamp on people for the third-third of their life promotes a terrible waste of talent, knowledge, and wisdom (a.k.a crystallized intelligence – see this article).

Here are three things that I think might happen if we stopped sending that talent, knowledge, and wisdom to the La-Z-Boy, park bench, or CCRC (Continuing Care Retirement Community).

1. We could redeploy that talent and wisdom to solve more of the mounting world’s problems. As author Neil Pasricha states: “There are far more problems and opportunities on this spinning planet than there are people to help with them so if you feel lost, follow your heart, find your ikigai, and remember the 4 S’s.

Social: Friends, peers, and coworkers who brighten our days and fulfill our social needs.

Structure: The alarm clock ringing because you have a reason to get up in the morning (ikigai), and the resulting satisfaction you get from earned time off.

Stimulation: Keeping our minds challenged by learning something new each day.

Story: Being part of something bigger than ourselves by joining a group whose high-level purpose is something you couldn’t accomplish on your own.

And stop worrying that you won’t ever be able to retire. You’ll be far better off if you don’t.

2. Reduce the burden on our out-of-control healthcare system. People age 55 and over accounted for 56% of total health spending in 2019, despite making up only 30% of the population. Active engagement, continuing to create, and reversing the role from sedentary self-indulgent retirees to active selfless contributors will mean a healthier, more vibrant elderly population with less extended morbidity and early frailty.

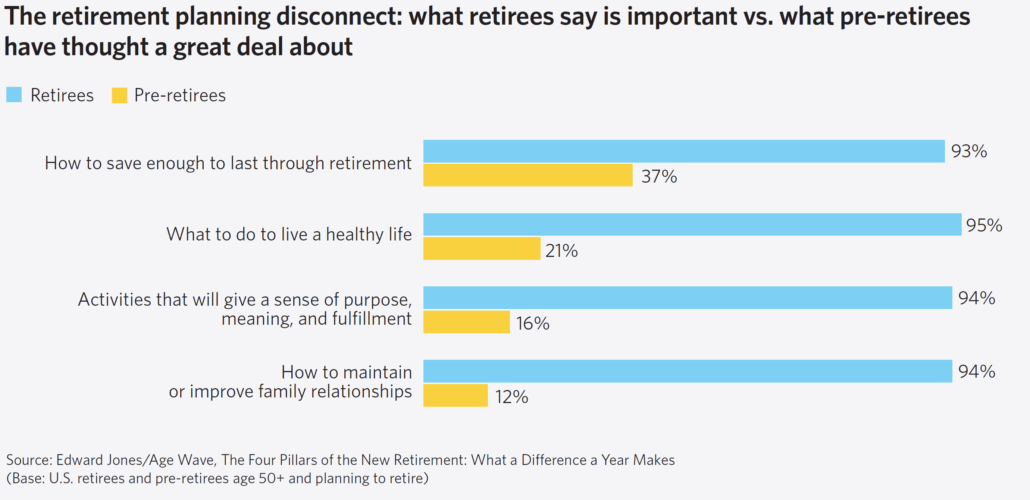

3. Return to generativity. We would reduce stagnation and inject more generativity which is “the propensity and willingness to engage in acts that promote the wellbeing of younger generations as a way of ensuring the long-term survival of the species.” Full-stop retirement steers us away from the level of generativity that volunteering, mentoring, engaging in community activism, and fostering other people’s growth can bring. Dr. Ken Dychtwald in his book “What Retirees Want” points out that individual Americans 65+ have 7.4 hours of leisure time per day equalling 195 billion hours of leisure a year or about 3.9 trillion hours over the next 20 years. He also points out that, despite that, older Americans spend under 4% of their discretionary time as volunteers, perhaps giving in to the lure of comfort, leisure, and reduced engagement.

I suspect this may not be a very popular position. Please share your thoughts. If you have any ideas on what we could do, or what would happen if we pivoted our perspectives on how to live out our third age, please share them with a comment below or an email to gary@makeagingwork.com.