Consider a “Quest”, Not a “Rest” in Your Retirement

“The good things in life are not things.”

So said a bumper-sticker on a Subaru I was behind as I was leaving Home Depot for the umpteenth time this week (it’s springtime spruce-up and planting time as I write).

I think the sticker is a mantra that’s resonating for a growing number of us boomers and pre-boomers.

At a time when my wife and I are “purging” in preparation for an eventual home downsize, this sticker hits home.

I sense there is a lot of major purging going on in boomer households these days. Purging comes up in a lot of conversations with fellow boomers and pre-boomers. Not as much as colonoscopies and knee, shoulder, and hip surgeries, but still at a pretty good clip.

We got another clue this week when we tried to drop off a pickup load of unneeded furniture at one of the local Goodwill facilities and they turned us away. They already have too much of that stuff, they said.

Egad! Nobody wants our stuff!

Doesn’t bode well for landfills, I’m afraid.

Not two hours after my Home Depot run, an article published by MarketWatch hit my news feed about a Google poll that revealed that the #1 question asked about retirement is “How Much Do I Need to Retire?”

Not surprising. But, money is “things” isn’t it?

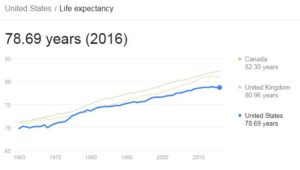

In our Western culture, we’re pretty wrapped around the axle about having enough money to enter into the mystical, uncharted territory called retirement. Because we’re living 20, 30 years longer than our grandparents/parents, we don’t much know what this territory is supposed to look like.

Up to this point, our lives had lots of societal/cultural checkpoints defining what to expect and what our lives should look like at each point. Then we hit this end-of-career wall and suddenly the guardrails and checkpoints disappear.

A metaphor by Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, co-author of “From AGE-ING to SAGE-ING”, A Revolutionary Approach to Growing Older” says it beautifully:

“From childhood to late adulthood, we’re like railroad trains that follow highly regular stretches of track to predictable destinations. Then, as elderhood approaches, we reach the end of the line, only to discover that management hasn’t had the foresight to lay any more track. We must get off the train and walk – but to where? What is our next destination?”

It seems because we haven’t been here before, we generally don’t plan for it except for guessing at having enough money to enter into it comfortably. And, logically, we don’t get much help in facing this new life void from the financial planner(s) who took us down the “paint-by-numbers” path to financial security. Their work is done and they can pridefully say “you did it – congratulations – now go forth and – do ???????”

The “do what” is the rub.

Financial planners usually stop there. Mental, physical, social, spiritual post-career elements are not “paint-by-numbers” issues and financial planners aren’t equipped to go there – or interested, thankfully. These soft-side components of planning your future apparently don’t pay very well – or at all.

There is one “what” we all know we don’t want. We don’t want our grandparents or perhaps even our parent’s retirement – isolated; park bench; bingo, bridge, and bocce ball; extended morbidity; urine-scented nursing home; walkers, wheelchairs and oxygen bottles.

There is one “what” we all know we don’t want. We don’t want our grandparents or perhaps even our parent’s retirement – isolated; park bench; bingo, bridge, and bocce ball; extended morbidity; urine-scented nursing home; walkers, wheelchairs and oxygen bottles.

But rather than plan on how to avoid that type of end-stage (Free hint: exercise, diet, social engagement, continuous learning, continuing to work, giving back/paying forward), we focus on a paint-by-the-numbers, magic figure designed to buy our way out of all that.

Then, a few years in, we find it ain’t quite like advertised. We begin to realize:

“Things” don’t buy legacies. “Things” buy disposal problems.

“Things” have never bought happiness. “Things” diffuse our energy.

“Things” don’t extend evolution. “Things” deplete our planet.

“Things” don’t build friendships. “Things” create comparisons and jealousies.

“Things” cause us to buy things we don’t really need, with money we don’t want to spend to impress people we don’t even like.

What’s real here?

Continuing through the entire MarketWatch article gets a little freaky and may cause mild-to-severe depression or the application of a corkscrew to a second bottle of wine.

For instance, the author states further in response to the #1 question: “ – most people won’t be able to retire the way they want with just $1 million.”

Just a million? Oh, really? Tell me it isn’t so!!

Finance guru Suze Orman says the magic retirement number is $5 million!

According to a recent survey from Charles Schwab, which looked at 1,000 401(k) plan participants nationwide, Americans believe they need $1.7 million to retire.

Enough already – can we bring this back down to earthly reality?

If my readership were representative of the general population, 60% of us would have zero, zilch, zip retirement assets. And only 11% of us would have $500,000 in retirement savings.

The median account balance for those with retirement savings accounts is estimated at $40,000.

Isn’t this latter figure close to “beans and weanies” and “under-a-bridge domicile” territory?

I know, as one of my readers, you do better than that – or aren’t hung up about it.

But just for grins: if you’ve got the $1.7 million in the bank, raise your hand.

OK – thanks and congratulations to all three of you!

Are we asking the right question?

If we were to flip the poll and ask “What is the least asked question about retirement?” what would you guess it would be.

I’m putting my money on: “Why do I have to retire?”

So maybe rather than succumb to the cultural pressure to enter into this unnatural act with its politically-inspired, artificial-finish-line, we should be asking: “Where does it say I have to do this retirement thing?”

I know. It’s a real ego bruise and not easy to tolerate the fact that you may be tagged as a loser because you’ve chosen not to retire – early or late. We’ve got a ways to go before un-retirement or semi-retirement will become the new prestige, replacing the current prestige tagged to early retirement.

But I sense we are getting there at a pretty good pace. I’m trying to accelerate that pace. That’s a big part of my quest.

How about a “quest” instead of “rest”?

Speaking of a quest, do you happen to have one for this period between middle age and true old age?

Speaking of a quest, do you happen to have one for this period between middle age and true old age?

When we succumb to the intrigue and hype of a traditional vocation-to-vacation retirement, we set ourselves up to slide insidiously to an early demise at a time when we can be kicking some serious tail with our accumulated skills, talents, wisdom and maturity.

We don’t have to look too far or too deep to see evidence that underscores the downsides of removing ourselves from the mainstream of life through retirement:

- We still “live too short and die too long” in this culture. Extended morbidity rates and early-on-set frailty are still too prevalent, costing us multiple-billions in late-life health care costs. The sedentary lifestyle of traditional retirement, the accompanying withdrawal from social engagement and learning, and lack of purpose combine to rob us of our full-life potential.

- Depression, divorce and suicide rates among the retired have reached alarming rates.

- Research done by the Blue Zones organization has shown that retirement doesn’t exist in the societies with the longest-living citizens where most citizens typically “live long and die short.”

We can turn to some notables for practical (and perhaps uncomfortable) perspectives on the concept of retirement:

- Strategic Coach founder, Dan Sullivan,74, refers to retirement as the “ultimate casualty” and advocates for “making your future bigger than your past” regardless of age.

- Walter Bortz, 89, semi-retired Stanford geriatric physician and author of seven books dealing with healthy aging refers to retirement in his book “Dare to Be 100” as “statutory senility.”

- Warren Buffett, still going strong at 87, says to avoid retirement. His rationale for avoiding retirement is straightforward and simple:

-

- You’re healthy

- You won’t have a fixed income

- You stay engaged and productive

- You’ll continue to mentor

- You can leverage your knowledge

- William Shatner , 88, refuses to retire and continues to work like his hair is on fire.

- Ken Langone (co-founder of Home Depot), 82, says: “ I’m not going to stop. I still go to work every day. If I didn’t have to sleep, I’d work 24 hours a day!

- Boone Pickens, 90, still keeps an office that he goes to every day saying, “Retirement isn’t an option for me. When you retire you have time to do what you love, and I love to work.“

- Fred Bartlit, 87, is a West Point grad, former Army Ranger, new author, strength-training fitness expert, back-bowl skier and a golfer who shoots his age. He still is a practicing attorney in the hugely successful law firm he founded.

These are all folks who seem to have a “quest” of some sort in their lives – and aren’t so much into “rest” as a lifestyle.

Somewhere along the road over the last 80 years or so, we’ve developed this attitude that we’re supposed to “rest” when we get older. For decades now, we’ve tagged 65 as the magic date at which this “rest period” should begin.

There is a multitude of problems with that.

Let’s start with the fact that our bodies and minds are not designed to “rest”. There’s nothing about aging that says we are supposed to stop challenging our bodies and minds. When we make “rest” our lifestyle, the insidiously destructive nature of inactivity begins to take over.

If we don’t use it, we lose it – body power or brain power.

Just look at the extended morbidity that still pervades our culture. We start “resting” and the decline gradually sets in.

We’ve been sold on the idea that we need to “slow down, enjoy life, take it easy, kick back, smell the roses, etc., etc.” Then, before you know it, we are in such decrepit shape that we can’t stoop over to smell the rose. Or our brain is gone and we wouldn’t know a rose scent from a bad case of flatulence.

No friends. No money. No purpose.

Those are the reasons that people die early, according to Dan Sullivan of Strategic Coach. All three seem to reflect “rest” instead of “quest”.

A “quest” is a sense of purpose with action behind it. It will almost automatically mean an increase in social engagement and more friends because any quest is going to involve touching lives in some way.

A quest can serve and still generate income. Author Mitch Anthony refers to it as a “playcheck” i.e. doing what you really want to do, are good at, that serves others and generates an income.

Start a quest

In mythology and fiction, a quest is a difficult journey toward a goal. It often involves a changed character of the hero.

You are the hero of your life. A quest in the third age brings to bear the components that help ensure a longer life with greater vitality by engaging mind and body, avoiding the deteriorating nature of the comfort zone, and deepening the social engagement so vital to good mental and physical health.

Evidence in support of the physical and mental advantages of a late-life sense of purpose/quest is overwhelming as is the evidence of the downside of not having one.

Let us know what your thoughts are on this, especially if you have a quest in your life. We’d love to know what your quest is and how you came to find it. Leave a comment below or email me at gary@makeagingwork.com.

Also, if you haven’t, subscribe to our weekly newsletter at www.makeagingwork.com and receive a copy of my free ebook entitled “Achieve Your Full-Life Potential: Five Easy Steps to Living Longer, Healthier, and With More Purpose.”

Here’s a taste: by way of encouraging continued and deeper learning, the authors remind us that we seriously underutilize our brain capacity and that we can counteract the ravages of brain cell disintegration associated with ageing by increasing neural connections through meditation (pick your own form) and lifelong learning.

Here’s a taste: by way of encouraging continued and deeper learning, the authors remind us that we seriously underutilize our brain capacity and that we can counteract the ravages of brain cell disintegration associated with ageing by increasing neural connections through meditation (pick your own form) and lifelong learning.

If I don’t look my age, which I don’t, it’s not my genetics. If I don’t act my age, which I don’t, it’s about my beliefs. If I don’t feel 77 – well I can’t say what that’s about because I’ve never been 77 before. I just know I’m more energized, motivated and purposeful than at any other point in my life and I’m convinced my biology is listening and tagging along.

If I don’t look my age, which I don’t, it’s not my genetics. If I don’t act my age, which I don’t, it’s about my beliefs. If I don’t feel 77 – well I can’t say what that’s about because I’ve never been 77 before. I just know I’m more energized, motivated and purposeful than at any other point in my life and I’m convinced my biology is listening and tagging along.

One, our venture beyond middle-age today is putting us into unfamiliar territory. We haven’t been here before – living this much longer. One hundred years ago, we checked out around 50, mostly succumbing to what retired Stanford geriatric physician Dr. Walter Bortz refers to as “lightning events” i.e. infectious diseases, injuries/accidents, malignancies, poisonings, wars.

One, our venture beyond middle-age today is putting us into unfamiliar territory. We haven’t been here before – living this much longer. One hundred years ago, we checked out around 50, mostly succumbing to what retired Stanford geriatric physician Dr. Walter Bortz refers to as “lightning events” i.e. infectious diseases, injuries/accidents, malignancies, poisonings, wars.

What I will rail against is off-the-cliff, labor-to-leisure, vocation-to-vacation retirement – the traditional model that emanated from a political decision in 1935, and that grew and became deeply embedded with the help of the financial services industry over the past 40-50 years.

What I will rail against is off-the-cliff, labor-to-leisure, vocation-to-vacation retirement – the traditional model that emanated from a political decision in 1935, and that grew and became deeply embedded with the help of the financial services industry over the past 40-50 years.

If retirement doesn’t seem to get even a fist pump for over half of those stepping into it, what’s missing? After all, it is that “nirvana” phase that consumed 35-40 years of our lives to get to and that promised us – at least in the financial services ads – a life of freedom, comfort, and fun.

If retirement doesn’t seem to get even a fist pump for over half of those stepping into it, what’s missing? After all, it is that “nirvana” phase that consumed 35-40 years of our lives to get to and that promised us – at least in the financial services ads – a life of freedom, comfort, and fun.