What’s It Really Like Being 80 Years Old? Surprise, surprise! Nothing changed.

As you might expect, turning 80 generates this question a lot.

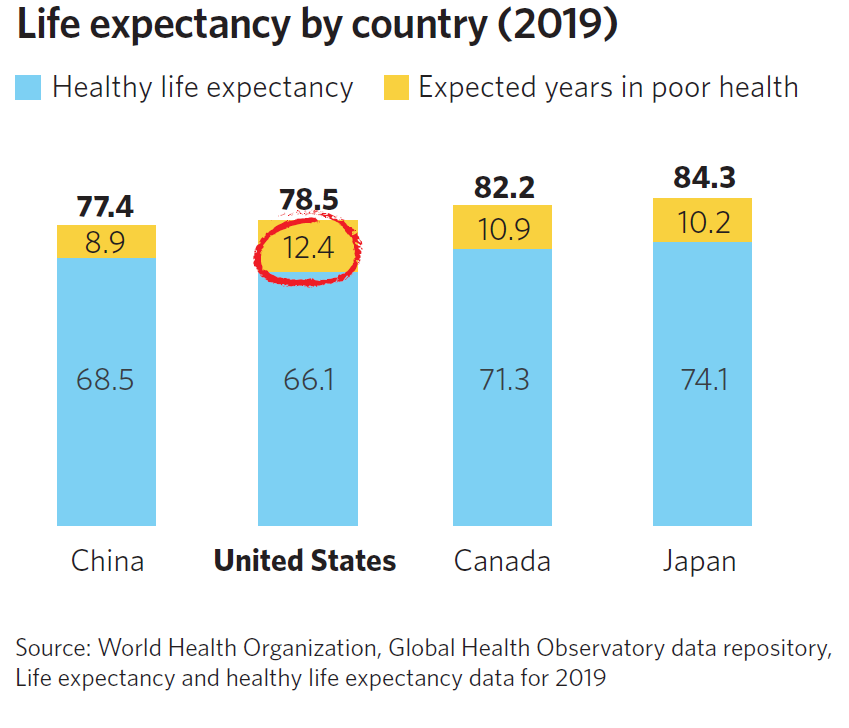

There’s a strange significance tied to it, perhaps because something less than half the U.S. population gets there.

Well, I just got there — with much more fanfare and celebration than I expected or deserved.

Having gotten there, I don’t find it to be much different than hitting 70 or 75, other than people seem to be more “surprised” that I’m 80 than they were when I was 78 or 79, thus speaking to the significant role that numbers play in our psyche.

Yes, I suspect I’m not different than most at this point. My eyesight is slipping a little, my tinnitus tends to rage more often, and being able to participate in conversations in a large, noisy environment ain’t gonna happen. But turning 80 didn’t flip those switches. They’ve been creeping in over the last several years.

It takes 5 minutes longer for the lower back stiffness to go away in the morning than 5 years ago.

Balance deterioration is a very real thing that I refuse to give in to with thrice-weekly aggressive strength training and daily balance and core strengthening exercises. Even at that, I’m aware of my deteriorating proprioception and am wiser about doing certain things, such as not being over 3′ off the ground on a ladder, or jumping off a moving golf cart or merry-go-round.

I suspect I’m not much different than others reaching the ripe numbers. I’ve gotten pretty good at not trying to control the uncontrollable. Many things that were important during the accumulation phase no longer matter. Other’s opinions don’t matter so much either. Material accumulation now reverts to a difficult disposal process. Some of the knowledge accumulated over many years begins to morph into worthwhile wisdom, sought out and welcomed by some, unacknowledged and ignored by most.

There’s this frustrating feeling of “having most of the answers” while nobody asks the questions.

Irrelevance comes easy.

It’s an easy trip into feeling irrelevant, with no help from a youth-obsessed culture. But, irrelevance is a choice and an easy narrative to buy into with all the calls to head for the park bench, retirement community, or pasture of your choice.

While admittedly not the sharpest knife in the drawer, I’ve got a hard drive between the temples crowded with acquired knowledge, experience, screw-ups, and victories that just might help someone. I can choose to sit on it and let it fade away in retirement mode, or I can put it out there for consideration for anyone who wants to partake.

So my 80 and all that follows is built on a simple daily mission to “breathe, learn, teach, repeat.” (Thank you, Dr. Ken Dychtwald, for that mantra.)

I have today. If I make it through today, it’ll be rinse and repeat a day at a time with a clear appreciation for the fact that tomorrow may not arrive.

Respecting the biology.

I know that I’m walking around in a 35-trillion-cell vessel that has proven its ability to last 122 years and 164 days. I’ll continue to give it the simple things it needs and see how long it can hold out, a day at a time, against that benchmark with no illusions of what the lifestyle choices in my first 50 years did to keep that from being a possibility.

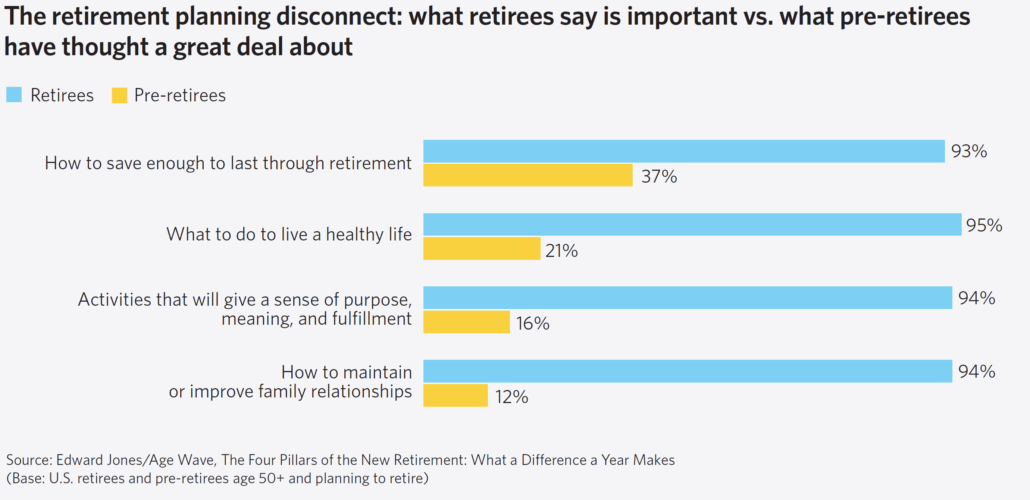

If I am an outlier in terms of vitality, energy, and sense of purpose or mission, I attribute much of that to having rejected the concept of retirement 40 years ago with the realization that biologically we either grow or decay.

Retirement is defined as going backward or withdrawing. I observed back then that many of the most successful and creative humans never left the creative process and were living longer. There seemed to be something fundamentally askew with retirement and the idea of going against our biology and the reason for being on the planet.

Is being 80 fun? Or a bummer?

In my aged opinion, it’s a choice. For me, it’s far short of being a bummer. Is it in the “fun” category? That would be a bit of a stretch. Fun gets redefined at this age. I find it in reading, contemplation, writing, and deep conversations with family and close friends.

And helping people understand it’s all just a number.